Hurricane Maria struck the island of Puerto Rico early on September 20, 2017, with 250-kilometer-per-hour winds, torrential rains and a storm surge as much as three meters excessive. In its wake: almost 3,000 folks useless, an nearly yearlong energy outage and over $90 billion in damages to properties, companies and important infrastructure, together with roads and bridges.

Geologist and diver Milton Carlo took shelter at his home in Cabo Rojo on the southwest nook of the island together with his spouse, daughter and toddler grandson. He watched the raging winds of the Category 4 hurricane raise his neighbor’s SUV into the air, and remembers these hours as a number of the worst of his life.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the most recent Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Thank you for signing up!

There was an issue signing you up.

For weeks, the remainder of the world was in the dead of night concerning the full extent of the devastation, as a result of Maria had destroyed the island’s foremost climate radar and nearly all cellphone towers.

Far away on the U.S. West Coast, in Santa Cruz, Calif., oceanographer Olivia Cheriton watched satellite tv for pc radar pictures of Maria passing over the devices she and her U.S. Geological Survey staff had anchored a couple of kilometers southwest of Puerto Rico. The devices, positioned offshore from the seaside city of La Parguera, had been there to trace air pollution circulating round a number of the island’s endangered corals.

More than half a yr glided by earlier than she realized the inconceivable destiny of these devices: They had survived and had captured knowledge revealing hurricane-related ocean dynamics that no scientist had ever recorded.

The wind-driven coastal currents interacted with the seafloor in a manner that prevented Maria from drawing chilly water from the depths of the ocean as much as the floor. The sea floor stayed as heat as bathwater. Heat is a hurricane’s gas supply, so a hotter sea floor results in a extra intense storm. As Cheriton discovered later, the phenomenon she stumbled upon possible performed a job in sustaining Maria’s Category 4 standing because it raked Puerto Rico for eight hours.

“There was absolutely no plan to capture the impact of a storm like Maria,” Cheriton says. “In fact, if we somehow could’ve known that a storm like that was going to occur, we wouldn’t have put hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of scientific instrumentation in the water.”

A storm’s path is guided by readily observable, large-scale atmospheric options comparable to commerce winds and high-pressure zones. Its depth, alternatively, is pushed by climate occasions contained in the hurricane and wave motion deep beneath the ocean’s floor. The findings by Cheriton and colleagues, revealed May 2021 in Science Advances, assist clarify why hurricanes usually get stronger earlier than making landfall and may due to this fact assist forecasters make extra correct predictions.

Reef air pollution

Cheriton’s authentic analysis goal was to determine how sea currents transport polluted sediments from Guánica Bay — the place the Lajas Valley drains into the Caribbean Sea — to the pristine marine ecosystems 10 kilometers west in La Parguera Natural Reserve, well-known for its bioluminescent waters.

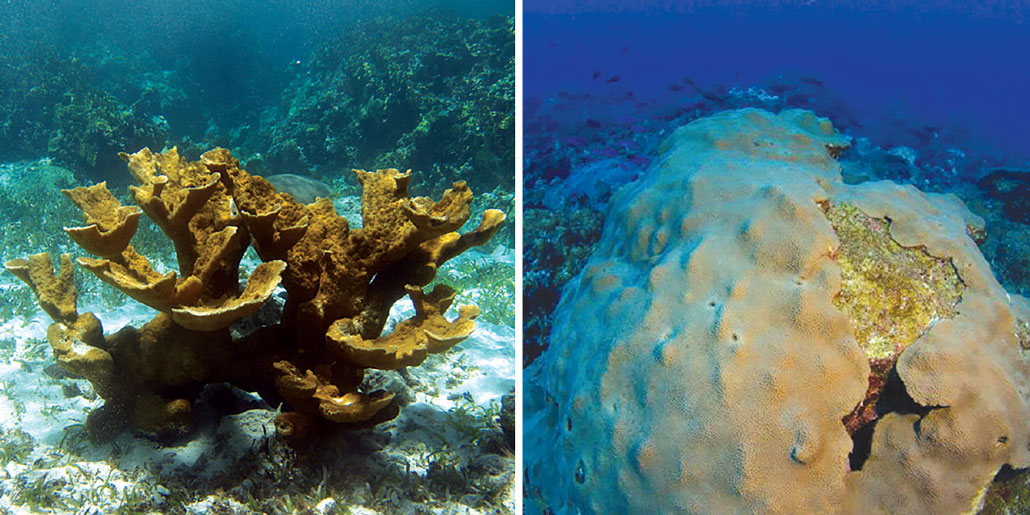

Endangered elkhorn and mountainous star corals, known as “the poster children of Caribbean reef decline” by marine geologist Clark Sherman, dwell close to shore in a number of the world’s highest recorded concentrations of now-banned industrial chemical compounds. Those polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, hinder coral replica, progress, feeding and defensive responses, says Sherman, of the University of Puerto Rico–Mayagüez.

Elkhorn coral (left) and mountainous star coral (proper) had been as soon as ubiquitous within the Caribbean. Their numbers have dropped enormously as a consequence of bleaching and illness. Pollution is partly guilty. FROM LEFT: NICK HOBGOOD/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS (CC BY-SA 3.0); NOAA FISHERIES

Elkhorn coral (left) and mountainous star coral (proper) had been as soon as ubiquitous within the Caribbean. Their numbers have dropped enormously as a consequence of bleaching and illness. Pollution is partly guilty. FROM LEFT: NICK HOBGOOD/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS (CC BY-SA 3.0); NOAA FISHERIES

Half of corals within the Caribbean have died since monitoring started within the Nineteen Seventies, and air pollution is a serious trigger, in accordance with an April 2020 examine in Science Advances. Of explicit curiosity to Cheriton, Sherman and their colleagues was whether or not the air pollution had reached deepwater, or mesophotic, reefs farther offshore, which might be a refuge for coral species that had been recognized to be dying in shallower areas.

The foremost artery for this air pollution is the Rio Loco — which interprets to “Crazy River.” It spews a poisonous runoff of eroded sediments from the Lajas Valley’s dust roads and occasional plantations into Guánica Bay, which helps a vibrant fishing group. Other potential contributors to the air pollution — oil spills, a fertilizer plant, sewage and now-defunct sugar mills — are the topic of investigations by public well being researchers and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

In June 2017, the staff convened in La Parguera to put in underwater sensors to measure and monitor the currents on this threatened marine atmosphere. From Sherman’s lab on a tiny islet overrun with iguanas the scale of home cats, he and Cheriton, together with staff chief and USGS analysis geologist Curt Storlazzi and USGS bodily scientist Joshua Logan, launched a ship into uneven seas.

Marine geologist Clark Sherman dives amid colonies of wholesome nice star corals, black corals, a big sea fan and a wide range of sponges alongside the steep island shelf of southwest Puerto Rico. Sherman helped examine whether or not air pollution was reaching these deepwater reefs.E. TUOHY/UNIV. OF PUERTO RICO–MAYAGÜEZ

Marine geologist Clark Sherman dives amid colonies of wholesome nice star corals, black corals, a big sea fan and a wide range of sponges alongside the steep island shelf of southwest Puerto Rico. Sherman helped examine whether or not air pollution was reaching these deepwater reefs.E. TUOHY/UNIV. OF PUERTO RICO–MAYAGÜEZ

At six websites close to shore, Storlazzi, Sherman and Logan dove to the seafloor and used epoxy to anchor stress gauges and batonlike present meters. Together the devices measured hourly temperature, wave top and present velocity. The staff then moved farther offshore the place the steep island shelf drops off at a 45-degree angle to a depth of 60 meters, however the heavy ocean chop scuttled their efforts to put in devices there.

In June 2017, analysis geologist Curt Storlazzi (left) and bodily scientist Joshua Logan (proper) put together to dive close to Puerto Rico’s Guánica Bay to put in devices for monitoring currents suspected of delivering air pollution to coral reefs.USGS

In June 2017, analysis geologist Curt Storlazzi (left) and bodily scientist Joshua Logan (proper) put together to dive close to Puerto Rico’s Guánica Bay to put in devices for monitoring currents suspected of delivering air pollution to coral reefs.USGS

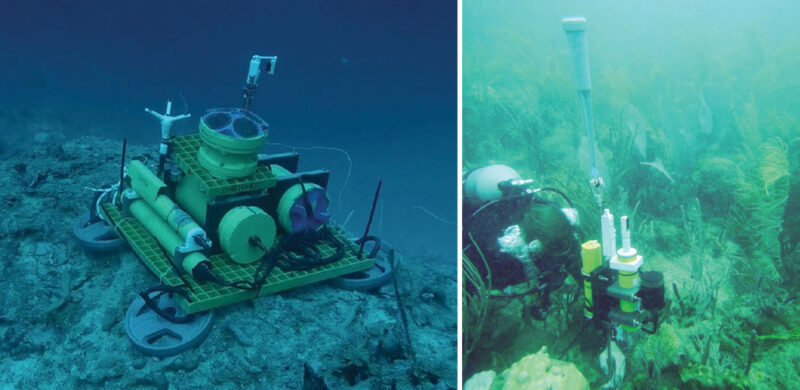

For assist working within the troublesome circumstances, Sherman enlisted two skilled divers for a second try: Carlo, the geologist and diving security officer, and marine scientist Evan Tuohy, each of the University of Puerto Rico–Mayagüez. The two had been capable of set up an important and largest piece, a hydroacoustic instrument comprising a number of drums fixed to a metallic grid, which tracked the course and velocity of currents each minute utilizing pulsating sound waves. A canister containing temperature and salinity sensors took readings each two minutes. Above this tools, an electrical thermometer prolonged to inside 12 meters of the floor, registering temperature each 5 meters vertically each few seconds.

The devices put in by Storlazzi, Logan and others collected surprising underwater ocean observations throughout Hurricane Maria. An acoustic Doppler present profiler (left) used pulsating sound waves to measure the course and velocity of currents on the shelf break and slope web site about 12 kilometers offshore of La Parguera. A Marotte present meter (proper) measured wave top, present velocity and temperature at six spots near shore.USGS

The devices put in by Storlazzi, Logan and others collected surprising underwater ocean observations throughout Hurricane Maria. An acoustic Doppler present profiler (left) used pulsating sound waves to measure the course and velocity of currents on the shelf break and slope web site about 12 kilometers offshore of La Parguera. A Marotte present meter (proper) measured wave top, present velocity and temperature at six spots near shore.USGS

Working in live performance, the devices gave a high-resolution, seafloor-to-surface snapshot of the ocean’s hydrodynamics on a near-continuous foundation. The tools needed to sit stage on the sloping seafloor in order to not skew the measurements and stay firmly in place. Little did the researchers know that the devices would quickly be battered by one of the vital damaging storms in historical past.

Becoming Maria

The phrase hurricane derives from the Caribbean Taino folks’s Huricán, god of evil. Some of the strongest of those Atlantic tropical cyclones start the place scorching winds from the Sahara conflict with moist subtropical air over the island nation of Cape Verde off western Africa. The worst of those atmospheric disturbances create extreme thunderstorms with large cumulonimbus clouds that flatten out towards the stratosphere. Propelled by the Earth’s rotation, they start to circle counterclockwise round one another — a phenomenon referred to as the Coriolis impact.

Weather circumstances that summer season had already spawned two monster hurricanes: Harvey and Irma. By late September, the extraordinarily heat sea floor — 29º Celsius or hotter in some locations — gave up its warmth vitality by the use of evaporation into Maria’s dashing winds. All hurricanes start as an space of low stress, which in flip sucks in additional wind, accelerating the rise of sizzling air, or convection. Countervailing winds referred to as shear can generally topple the cone of moist air spiraling upward. But that didn’t occur, so Maria continued to develop in dimension and depth.

Meteorologists hoped that Maria would lose drive because it moved throughout the Caribbean, weakened by the wake of cooler water Irma had churned up two weeks earlier. Instead, Maria tracked south, steaming towards the japanese Caribbean island of Dominica. Within 15 hours of constructing landfall, its most sustained wind velocity doubled, reaching a house-leveling 260 kilometers per hour. That doubling intensified the storm from a milder (nonetheless harmful) Category 1 to a robust Category 5.

NOAA’s laptop forecasting fashions didn’t anticipate such fast intensification. Irma had additionally raged with unexpected depth.

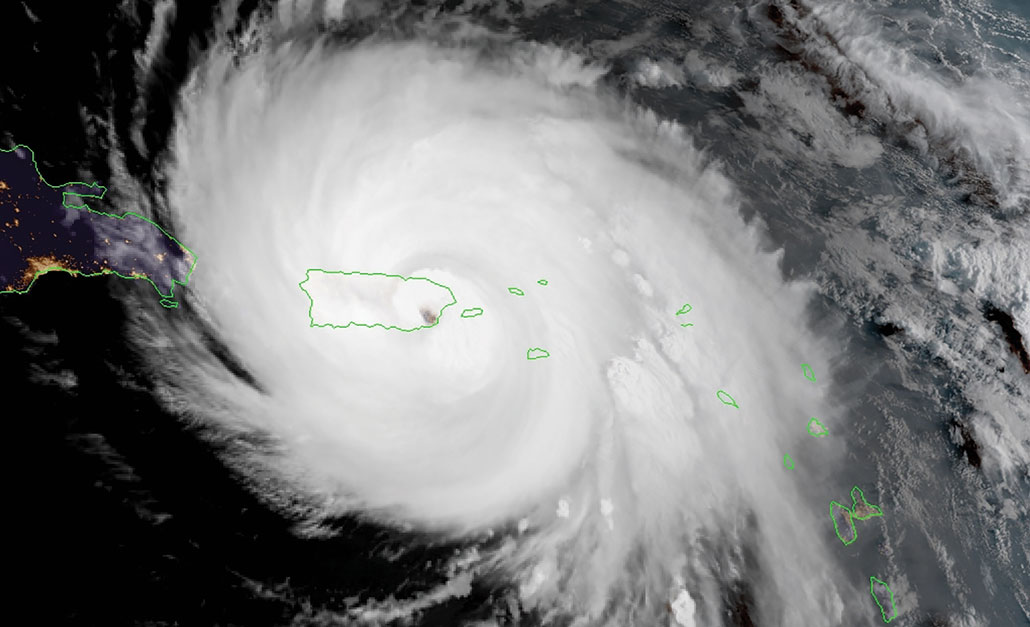

After putting Dominica arduous, Maria’s eyewall broke down, changed by an outer band of whipping thunderstorms. This barely weakened Maria to 250 kilometers per hour earlier than it hit Puerto Rico, whereas increasing the diameter of the storm’s eyewall — the realm of sturdy winds and heaviest precipitation — to 52 kilometers. That’s near the width of the island.

Hurricane Maria made landfall on Puerto Rico early within the morning on September 20, 2017, and lower throughout the island diagonally towards the northwest. Its eyewall generated most sustained winds of 250 kilometers per hour and spanned nearly the width of the island.CIRA/NOAA

Hurricane Maria made landfall on Puerto Rico early within the morning on September 20, 2017, and lower throughout the island diagonally towards the northwest. Its eyewall generated most sustained winds of 250 kilometers per hour and spanned nearly the width of the island.CIRA/NOAA

It’s nonetheless not absolutely understood why Maria had instantly gone berserk. Various theories level to the affect of sizzling towers — convective bursts of warmth vitality from thunderclouds that punch up into the stratosphere — or deep heat swimming pools, buoyant freshwater eddies spilling out of the Amazon and Orinoco rivers into the Atlantic, the place currents carry these pockets of hurricane-fueling warmth to the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea.

But although these smaller-scale occasions could have a big effect on depth, they aren’t absolutely accounted for in climate fashions, says Hua Leighton, a scientist on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s hurricane analysis division and the University of Miami’s Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies. Leighton develops forecasting fashions and investigates fast intensification of hurricanes.

“We cannot measure everything in the atmosphere,” Leighton says.

Without correct knowledge on all of the elements that drive hurricane depth, laptop fashions can’t simply predict when the catalyzing occasions will happen, she says. Nor can fashions account for all the things that occurs contained in the ocean throughout a hurricane. They don’t have the info.

Positioning devices simply earlier than a hurricane hits is a serious problem. But NOAA is making progress. It has launched a brand new era of hurricane climate buoys within the western North Atlantic and distant management floor sensors known as Saildrones that study the air-sea interface between hurricanes and the ocean (SN: 6/8/19, p. 24).

Underwater, NOAA makes use of different drones, or gliders, to profile the huge areas frequently traversed by tropical storms. These gliders collected 13,200 temperature and salinity readings in 2020. By distinction, the devices that the staff set in Puerto Rico’s waters in 2017 collected over 250 million knowledge factors, together with present velocity and course — a uncommon and particularly precious glimpse of hurricane-induced ocean dynamics at a single location.

A special view

After the storm handed, Storlazzi was certain the hurricane had destroyed his devices. They weren’t designed to take that form of punishment. The gadgets usually work in a lot calmer circumstances, not the huge swells generated by Maria, which might enhance water stress to a stage that might nearly definitely crush instrument sensors.

But remarkably, the devices had been battered however not misplaced. Sherman, Carlo and Touhy retrieved them after Maria handed and put them in crates awaiting the analysis group’s return.

Milton Carlo (left) and Evan Tuohy (proper), proven in an earlier deepwater dive, helped place the current-monitoring devices on the hard-to-reach websites the place hurricane knowledge had been collected.MIKE ECHEVARRIA

Milton Carlo (left) and Evan Tuohy (proper), proven in an earlier deepwater dive, helped place the current-monitoring devices on the hard-to-reach websites the place hurricane knowledge had been collected.MIKE ECHEVARRIA

When Storlazzi and USGS oceanographer Kurt Rosenberger pried open the instrument casings in January 2018, no water gushed out. Good signal. The electronics appeared intact. And the lithium batteries had powered the rapid-fire sampling enterprise for the whole six-month length. The researchers rapidly downloaded a flood of information, backed it up and began transmitting it to Cheriton, who started sending again plots and graphs of what the readings confirmed.

Floodwaters from the huge rains introduced by Maria had pushed an entire lot of polluted sediment to the reefs exterior Guánica Bay, spiking PCB concentrations and threatening coral well being. As of some months after the storm, the air pollution hadn’t reached the deeper reefs.

Then the researchers realized that their knowledge informed one other story: what occurs underwater throughout a large hurricane. They presumed that different researchers had beforehand captured a profile of the churning ocean depths beneath a hurricane on the fringe of a tropical island.

Remarkably, that was not the case.

“Nobody’s even measured this, let alone reported it in any published literature,” Cheriton says. The staff started to discover the hurricane knowledge not realizing the place it would lead.

“What am I looking at here?” Cheriton stored asking herself as she plotted and analyzed temperature, present velocity and salinity values utilizing laptop algorithms. The temperature gradient that confirmed the ocean’s inside or underwater waves was completely different than something she’d seen earlier than.

Oceanographer Olivia Cheriton realized that knowledge on ocean currents informed a brand new story about Hurricane Maria.O.M. CHERITON

Oceanographer Olivia Cheriton realized that knowledge on ocean currents informed a brand new story about Hurricane Maria.O.M. CHERITON

During the hurricane, the highest 20 meters of the Caribbean Sea had constantly remained at or above 26º C, a couple of levels hotter than the layers beneath. But the floor waters ought to have been cooled if, as anticipated, Maria’s winds had acted like an enormous spoon, mixing the nice and cozy floor with chilly water stirred up from the seafloor 50 to 80 meters beneath. Normally, the cooler floor temperature restricts the warmth provide, weakening the hurricane. But the chilly water wasn’t reaching the floor.

To attempt to make sense of what she was seeing, Cheriton imagined herself inside the info, in a protecting bubble on the seafloor with the devices as Maria swept over. Storlazzi labored alongside her analyzing the info, however targeted on the sediments circulating across the coral reefs.

Cheriton was listening to “An Awesome Wave” by indie-pop band Alt-J and getting goosebumps whereas the info swirled earlier than them. Drawing on instincts from her undergraduate astronomy coaching, she targeted her thoughts’s eye on a constellation of information overhead and informed Storlazzi to do the identical.

“Look up Curt!” she mentioned.

Up on the crest of the island shelf, the place the seafloor drops off, the present velocity knowledge revealed a broad stream of water gushing from the shore at nearly 1 meter per second, as if from a hearth hose. Several hours earlier than Maria arrived, the wind-driven present had reversed course and was now transferring an order of magnitude sooner. The dashing floor water thus grew to become a barrier, trapping the chilly water beneath it.

As a outcome, the floor stayed heat, growing the drive of the hurricane. The cooler layers beneath then began to pile up vertically into distinct layers, one on prime of the opposite, beneath the gushing waters above.

Cheriton calculated that with the hearth hose phenomenon the contribution from coastal waters on this space to Maria’s depth was, on common, 65 % higher, in contrast with what it could have been in any other case.

Oceanographer Travis Miles of Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J., who was not concerned within the analysis, calls Cheriton and the staff’s work a “frontier study” that attracts researchers’ consideration to near-shore processes. Miles can relate to Cheriton and her staff’s unintended hurricane discovery from private expertise: When his water high quality–sampling gliders wandered into Hurricane Irene’s path in 2011, they revealed that the ocean off the Jersey Shore had cooled in entrance of the storm. Irene’s onshore winds had induced seawater mixing throughout the broad continental shelf and lowered sea floor temperatures.

The Puerto Rico knowledge present that offshore winds over a steep island shelf produced the alternative impact and will assist researchers higher perceive storm-induced mixing of coastal areas, says NOAA senior scientist Hyun-Sook Kim, who was not concerned within the analysis. It might help with figuring out deficiencies within the laptop fashions she depends on when offering steerage to storm-tracking meteorologists on the National Hurricane Center in Miami and the Joint Typhoon Warning Center in Hawaii.

And the surprising findings additionally might assist scientists get a greater deal with on coral reefs and the function they play in defending coastlines. “The more we study the ocean, especially close to the coast,” Carlo says, “the more we can improve conditions for the coral and the people living on the island.”