On a Saturday in May in Flint, Mich., residents took seats in one of three rings of chairs at a local food bank. The 50 or so participants, spanning three generations, would spend time that morning sharing stories and practicing deep listening as part of a healing circle. It’s one component of a wider community-based movement to build relationships and challenge racist beliefs and systems.

Healing circles are a space to foster community, says Lynn Williams, the director of equity and community engagement at the Community Foundation of Greater Flint, who helped organize the event that morning. The circles allow room for “healing of trauma from systems, from oppression, from negativity,” she says. And they provide a place to tell a community’s full story, to “highlight the assets and the cultural contributions.”

The circles are one way to let people know they matter when society keeps telling them they don’t.

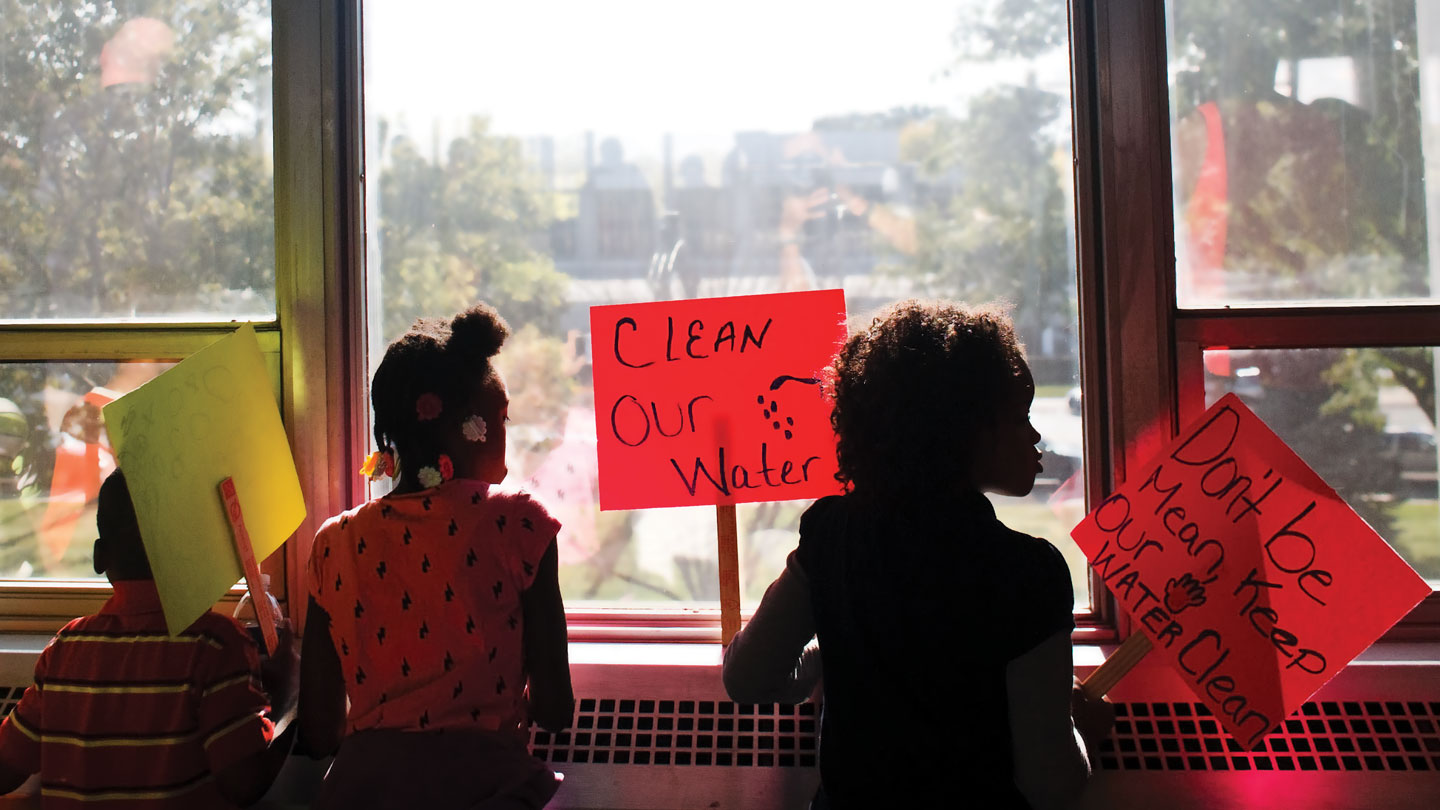

The residents of Flint — a city with a majority Black population and many people experiencing poverty — know this disregard well. In April 2014, to cut costs, state officials switched the city’s water source from Lake Huron to the Flint River without an adequate treatment plan. The public health catastrophe that has followed “is a story of government failure, intransigence, unpreparedness, delay, inaction and environmental injustice,” according to the final report from the Flint Water Advisory Task Force, commissioned to find the causes of the water disaster. The human-made crisis turned a necessity into a hazard for the residents of the city, which had a population of around 99,000 at the time. The lack of proper treatment exposed people to bacteria, excessive disinfection chemicals and lead.

2023-11-16 08:00:00

Post from www.sciencenews.org