Once upon a time, Spain’s hilltop Alhambra palace glittered with gold. Over the centuries, although, the Islamic citadel’s ornate, gilded constructions on its ceilings and elsewhere fell into disrepair, with curious purple splotches marring them. The stains’ origins have been a thriller. But scientists say they now perceive the chemistry behind the purple tinge.

Analyses reveal that because the gilding decayed, it shaped gold spheres invisible to the bare eye which can be answerable for the purple shade, the researchers report on-line September 9 in Science Advances. The discovering might have implications for understanding how different artwork and structure degrades with time.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the newest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Thank you for signing up!

There was an issue signing you up.

Medieval artisans crafted some Alhambra ceilings to appear like a cave’s stalactites, then gilded them with a layer of tinfoil topped by a gold-and-silver alloy. In the nineteenth century, individuals coated the degrading gilding with gypsum, a white mineral present in plaster.

Geologist Carolina Cardell of Spain’s University of Granada first observed purple stains on the gypsum in 1993, however she and her colleagues didn’t have the instruments to grasp the splotches again then. Things modified when the college obtained two sorts of electron microscopes. The microscopes couple to different devices that reveal a pattern’s chemical parts and compounds on the nanoscale.

Faint purple stains (arrow) brought on by gold spheres invisible to the bare eye mar decorations on constructions in Spain’s Alhambra palace. The blue shade is the pigment lapis lazuli.C. Drahl

Faint purple stains (arrow) brought on by gold spheres invisible to the bare eye mar decorations on constructions in Spain’s Alhambra palace. The blue shade is the pigment lapis lazuli.C. Drahl

Cardell’s colleague Carmen Navarrete, a former head of restoration on the Alhambra, died earlier than the group may get solutions. Cardell and electron microscopy skilled Isabel Guerra, additionally of the University of Granada, soldiered on with out Navarrete to look at layers of gilding, gypsum and stains from the Alhambra. “We said we have to finish this and dedicate this work to her,” Cardell says.

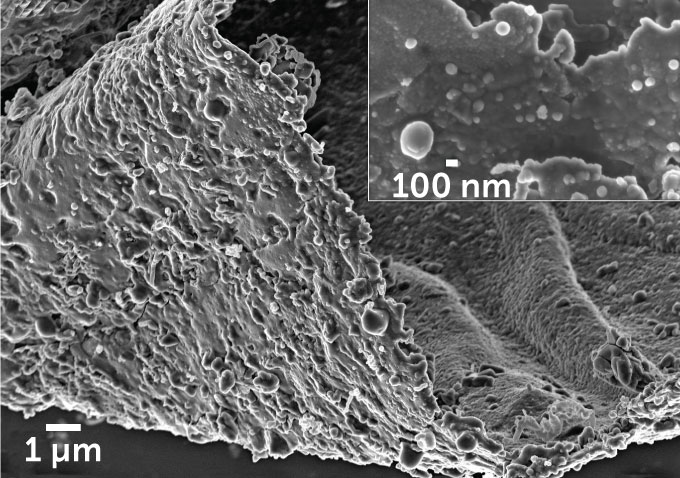

Dots in microscope photos of the gypsum proved to be pure gold nanospheres, most of that are about 70 nanometers extensive. Nanoparticles’ colours rely upon their dimension, which influences their interactions with mild, and 70 nanometers is the fitting dimension for a purple hue.

Based on the weather and compounds detected, Cardell and Guerra conclude that a number of corrosion processes shaped the nanoparticles (SN: 3/21/15). Though pure gold is immune to corrosion, the gold-and-silver alloy within the Alhambra shouldn’t be. Flaws within the gilding let in moisture, together with the Mediterranean’s chloride-rich airborne sea spray. That created chemical contacts between the gilding’s metals akin to these in a battery. As a outcome, the underlying tin corroded, pushing its method by way of defects within the alloy and protecting a number of the gold as grayish grime.

In this electron microscope picture, gold nanospheres (close-up proven in field) detach from the floor of a broken gold-silver alloy layer of gilding on Spain’s Alhambra citadel.C. Cardell and I. Guerra/University of GranadaIn this electron microscope picture, gold nanospheres (close-up proven in field) detach from the floor of a broken gold-silver alloy layer of gilding on Spain’s Alhambra citadel.C. Cardell and I. Guerra/University of Granada

In this electron microscope picture, gold nanospheres (close-up proven in field) detach from the floor of a broken gold-silver alloy layer of gilding on Spain’s Alhambra citadel.C. Cardell and I. Guerra/University of GranadaIn this electron microscope picture, gold nanospheres (close-up proven in field) detach from the floor of a broken gold-silver alloy layer of gilding on Spain’s Alhambra citadel.C. Cardell and I. Guerra/University of Granada

Different components of the gold have been thus uncovered to completely different oxygen concentrations. That triggered additional chemical reactions that dissolved a number of the gold, paving the best way for the spheres’ formation. Those spheres ended up settling within the gypsum, Cardell says.

“The level of detail of the study is phenomenal,” says Francesca Casadio, who heads the conservation science division on the Art Institute of Chicago. “Others are going to see these purplish hues and they are going to have a rubric to understand the phenomenon.”

Few experiences of purple gold on broken art work and structure exist. Cardell thinks that the white gypsum coating added to the Alhambra within the nineteenth century made the purple simple to note. “We think that this purple color… is more widespread than people imagine.”