Signals buried deep in knowledge from gravitational wave observatories indicate a collision of two black holes that had been clearly born in other places.

Almost all of the spacetime ripples that experiments just like the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO, see come from collisions amongst black holes and neutron stars which might be in all probability shut members of the family (SN: 1/21/21). They had been as soon as pairs of stars born on the identical time and in the identical place, finally collapsing to kind orbiting black holes or neutron stars in previous age.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the newest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Thank you for signing up!

There was an issue signing you up.

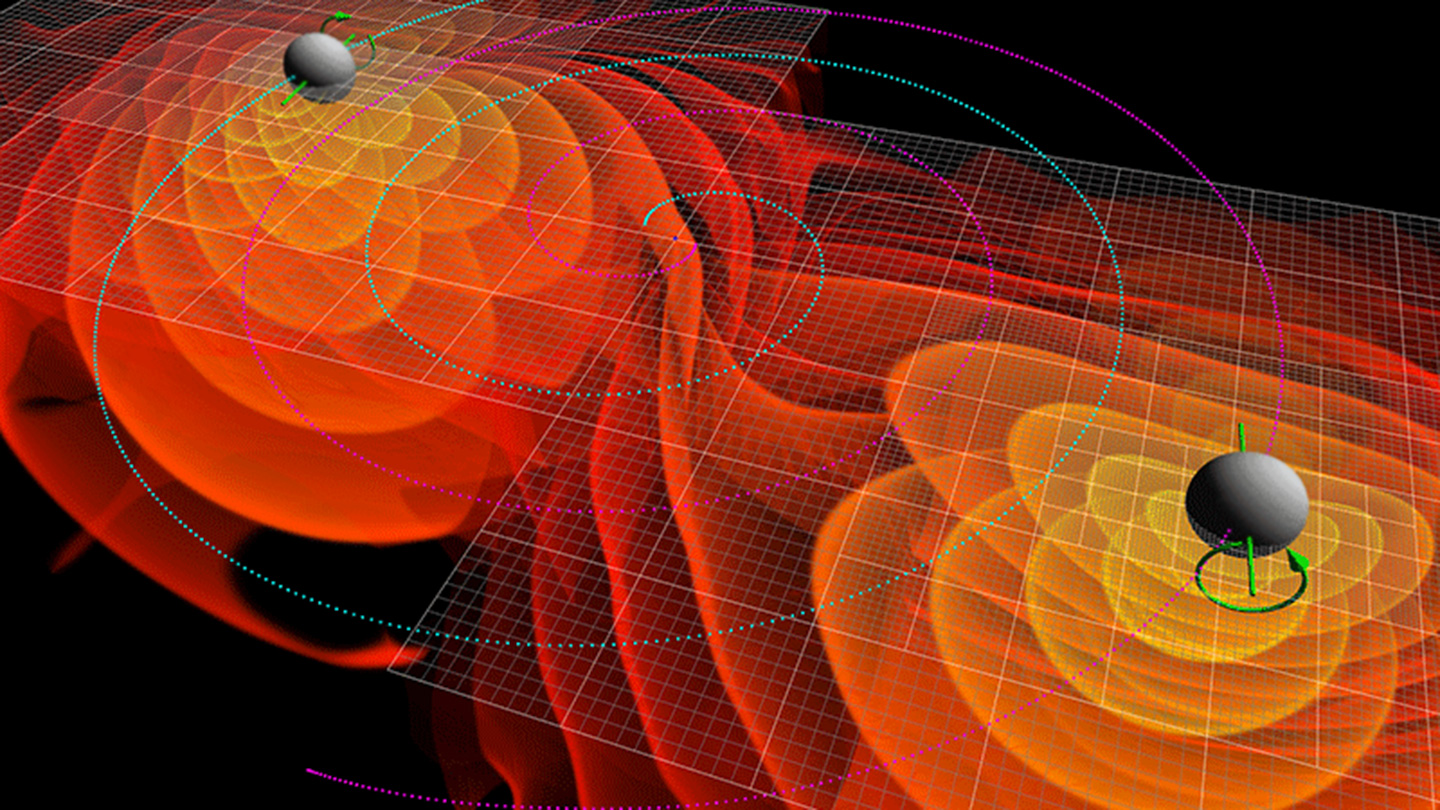

Now, a newly famous marriage of black holes, present in present knowledge from U.S.–based mostly LIGO and its sister observatory Virgo in Italy, appears to be of an unrelated pair. Evidence for this stems from how they had been spinning as they merged into one, researchers report in a paper in press at Physical Review D. Black holes which might be born in the identical place are inclined to have their spins aligned, like a pair of toy tops spinning on a desk, as they orbit one another. But the pair on this case haven’t any correlation between their respective spins and orbits, implying that they had been born in other places.

“This is telling us we’ve finally found a pair of black holes that must come from the non-grow-old-and-die-together channel,” says Seth Olsen, a physicist at Princeton University.

Previous occasions which have turned up in gravitational wave observations present again holes merging that aren’t completely aligned, however most are shut sufficient to strongly indicate household connections. The new detection, which Olsen and colleagues discovered by sifting via knowledge that the LIGO-Virgo collaboration launched to the general public, is completely different. One of the black holes is successfully spinning the other way up.

That can’t simply occur except the 2 black holes come from separate locations. They in all probability met late of their stellar lives, in contrast to the black gap littermates that appear to make up the majority of gravitational wave observations.

In addition to the merger between unrelated black holes, Olsen and his collaborators recognized 9 different black gap mergers that had slipped via the prior LIGO-Virgo research (SN: 8/4/21).

“This is actually the nice thing about this type of analysis,” says LIGO scientific collaboration spokesperson Patrick Brady, a physicist on the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee who was not affiliated with the brand new research. “We deliver the data in a format that can be used by other people and then [they] will have access to try out new techniques.”

To compile so many new alerts in knowledge that had already been gone over by different researchers, Olsen’s group lowered the analytical bar somewhat.

“Out of the 10 new ones,” Olsen says, “there are about three of them, statistically, that probably come from noise,” slightly than being definitive black gap merger detections. Assuming that the merger of black holes strangers isn’t among the many errant alerts, it nearly actually tells a story of black gap histories distinct from the others seen to this point.

“It would be [extremely] unlikely for this to come from two black holes that have been together for their whole lifespan,” Olsen says. “This must have been a capture. That’s cool because we’re finally able to start probing that region of the [black hole] population.”

Brady notes that “we don’t understand the theory [of black hole mergers] well enough to be able to confidently predict all of these types of things.” But the latest research might level to new and attention-grabbing alternatives in gravitational wave astronomy. “Let’s follow this clue to see if it really is reflecting something rare,” he says. “Or if not, well, we’ll learn other things.”