How Far the Light Reaches

Sabrina Imbler

Little, Brown & Co., $27

In How Far the Light Reaches, Sabrina Imbler exhibits us that the ocean, in all its thriller and dazzling glory, is queer — that’s, the life that takes form there challenges how we landlubbers understand methods of being. This assortment of essays tells the tales of 10 sea creatures, with Imbler, a queer and mixed-race author, weaving in tales of their very own household, self-discovery, sexuality and therapeutic. The profiled animals, usually considered unusual or alien, rework into recognizable emblems of id, neighborhood and queer pleasure on this delectable amalgam of memoir and science journalism.

Imbler begins with a confession: “The truth is that I was asked to leave the Petco, but I told everyone I was banned.” Thirteen-year-old Imbler had staged a protest within the retailer, trying to persuade clients to not purchase goldfish bowls. The bowls, Imbler writes, condemn the fish to a truncated life in a clear coffin, wherein they may die remoted, starved of oxygen and poisoned with ammonia from their very own urine.

But unencumbered by the confines of a bowl, the fish thrive. When bored pet house owners dump goldfish in lakes or rivers, the fish can balloon to the scale of jugs of milk. They are “so good at living they have become an ecological menace,” breeding with abandon, uprooting backside dwellers, and fomenting bacterial progress and algal blooms, Imbler writes.

Yet Imbler can’t assist however admire the feral goldfish’s resilience: “I see something that no one expected to live not just alive but impossibly flourishing.”

Survival amongst unthinkable circumstances is a theme widespread to all of the profiled animals. Take the yeti crab (Kiwa puravida), which, after studying this guide, I now proclaim a queer icon (step apart, the Babadook). In the frigid darkish, about 1,000 meters under the ocean floor, the crab finds solace close to hydrothermal vents.

Such sizzling spots foster life in a desolate wasteland. Heat and chemical substances from contained in the Earth maintain an ecosystem of crabs, clams, mussels, tube worms and extra. There, in true queer trend, Okay. puravida “dances to live,” Imbler writes. The yeti crab throws its claws within the air and waves ’em prefer it simply don’t care. In doing so, it’s “farming” the micro organism that it eats, which cling to the crab’s bristly claws. Waving the claws in a gradual however regular rhythm ensures the micro organism get vitamins.

In telling the crab’s story, Imbler reminisces on their quest to search out neighborhood after shifting to Seattle in 2016. Feeling alone among the many largely white folks they met, Imbler found a month-to-month celebration known as Night Crush, thrown by and for queer folks of shade. Night Crush turned Imbler’s personal hydrothermal vent — an oasis warmed by folks dancing in mesh, sequins, glitter and pleasure. “As queer people, we get to choose our families,” Imbler writes. “Vent bacteria, tube worms, and yeti crabs just take it one step further. They choose what nourishes them.”

Subscribe to Science News

Get nice science journalism, from essentially the most trusted supply, delivered to the doorstep.

Imbler seems to be to the ocean to discover all features of household. The purple octopus (Graneledone boreopacifica), as an example, provides insights on motherhood. During a four-and-a-half-year brooding interval, the longest identified for any animal, the octopus starves herself to dying, foregoing looking to guard her eggs (SN: 7/30/14).

Through the octopus’ saga, Imbler displays on their very own mom, who moved to the United States from Taiwan as a baby. Imbler’s mom felt like she was on “a new planet.” To survive, she realized to wish to be as white and “American” as attainable, and as skinny as attainable — traumas inherited by Imbler, who developed an consuming dysfunction.

In their restoration, Imbler has realized their mom’s want for them to be skinny, although damaging, was, in a method, an act of affection: “She wanted me to be skinny so things would be easier. White, so things would be easier. Straight, so things would be easy, easy, easy. So that unlike her, no one would ever question my right to be here, in America.”

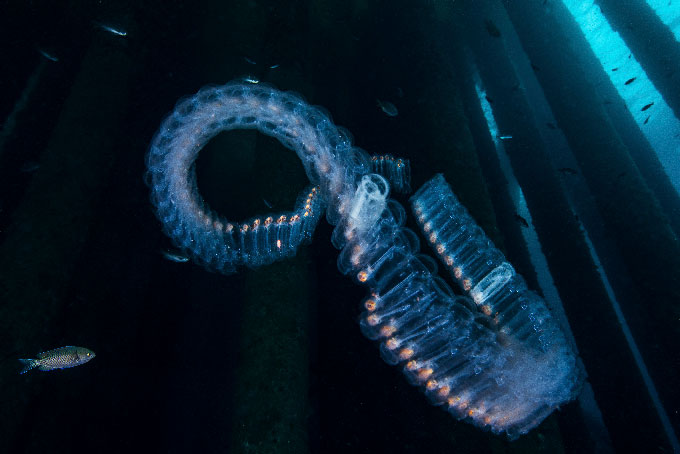

A series of salps floats off the coast of California within the Pacific Ocean.Brook Peterson/Stocktrek Images/Getty Images Plus

A series of salps floats off the coast of California within the Pacific Ocean.Brook Peterson/Stocktrek Images/Getty Images Plus

It is with that very same grace, readability and tenderness that Imbler crafts the guide’s different essays, whether or not it’s meditating on their very own gender expression by the cuttlefish’s mastery of metamorphosis or analyzing their expertise of sexual assault by the sand striker, an ambush predator of the seafloor.

Like a goldfish confined by a bowl, I’m confined by my phrase depend and may’t say every part I wish to about this must-read guide. So I’ll finish on one remaining perception. In one essay, Imbler introduces salps. These jelly-like blobs exist as a colony of a whole bunch of an identical salps joined in a sequence. The creatures don’t transfer in a single synchronized effort. “Salps allow each individual to jet at its own pace in the same general direction,” Imbler writes. “It is not as fast as coordinated strokes, but it’s more sustainable long-term, each individual sucking and spurting as it pleases.”

This thought of 1 collective, made up of people marching towards a standard trigger at their very own tempo, is one which queer folks and different marginalized teams know effectively — whether or not creating neighborhood or protesting for civil rights. And it’s a notion that Imbler imparts upon their reader: “We may all move at different paces, but we will only reach the horizon together.”

Buy How Far the Light Reaches from Bookshop.org. Science News is a Bookshop.org affiliate and can earn a fee on purchases made out of hyperlinks on this article.