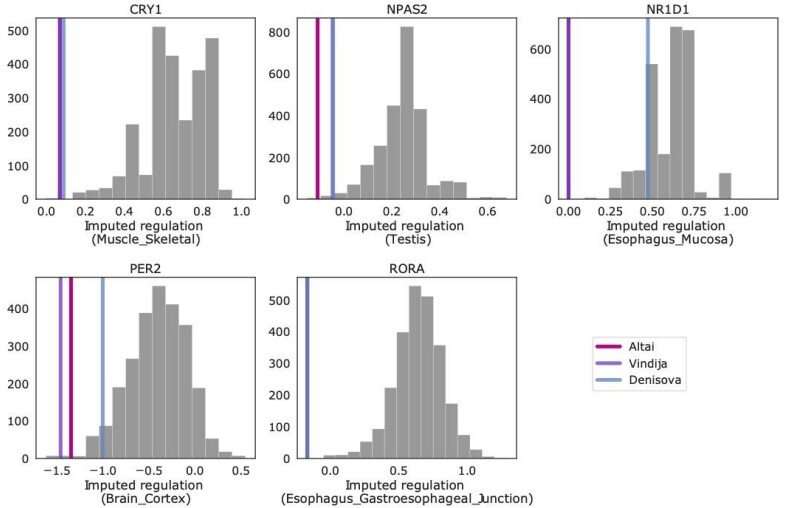

Many circadian genes are divergently regulated between modern humans and archaic hominins. Comparison of the imputed regulation of core circadian genes between 2,504 humans in 1,000 Genomes Phase 3 (gray bars) and three archaic individuals (vertical lines). For each core circadian gene, the tissue with the lowest average P-value for archaic difference from humans is plotted. Archaic gene regulation is at the extremes of the human distribution for several core genes: CRY1, PER2, NPAS2, NR1D1 RORA. Credit: (2023). DOI: 10.1101/2023.02.03.527061

A team of epidemiologists and geneticists from Vanderbilt University, the University of Pennsylvania and the University of California has found evidence that suggests modern humans mating with Neanderthals may have gained an ability to adapt to differences in the amount of daylight hours in Eurasia.

The group studied Neanderthal genes left in the human genome while looking for those that might impact the circadian rhythm, and found several that suggested mating with Neanderthal natives might have benefited newly arriving humans in ways that have not been known before. Their work has been published on the bioRxiv preprint server.

Prior research has shown that ancestors of Neanderthals arrived in Eurasia before modern humans. Those that adapted to the vastly different environment (compared to Africa) survived, while those that did not perished. One such adaptation would have been changes to the circadian rhythm to align with changes in seasons and the associated length of days.

As the Neanderthals persisted, their genomes would have evolved to allow them to live in places where days could grow very short and cold at times, and hot and long at others. Later, as the ancestors of modern humans began arriving in Eurasia, some of them procreated with the Neanderthals already living there. Researchers believe that some of the Neanderthal genome that was related to adapting to a Eurasian environment joined with the modern human genome, allowing human offspring to better deal with the environment in which they were born.

In this new study, the research group sought evidence of adaptations by the Neanderthal that helped them survive in Eurasia, and further evidence that they passed along some of those genes to modern humans. They found 28 identifiable circadian genes in the Neanderthal pool and 16 circadian genes that had been passed on to modern humans. In the second set of genes, they found that the shift in the circadian rhythm in the modern human recipients moved in the same direction, pushing them to become morning people.

© 2023 Science X Network

2023-02-18 10:00:03

Original from phys.org

A recent study published inScience Advances has identified a unique set of genes in Neanderthals that suggests the species was well adapted to the extreme daylight hours found in Eurasia. The study concluded that these genes are unique to Neanderthals, allowing them to better acclimatize to the extreme hours of daylight in the regions they lived in.

The researchers used genomic data from Neanderthals, modern humans, and other human ancestors to study the differences in the DNA of the species. They compared the gene variant frequencies in Neanderthals with those seen in modern humans and earlier human relatives, as well as two Neanderthal specimens.

The results of the analysis showed that Neanderthals had a unique set of genes, associated with adaptation to Eurasian daylight hours. This set of genes is not common among modern humans, suggesting that Neanderthals were well adapted to life in the regions, with longer nights and shorter days.

It is thought that this adaptation was a key factor in the success and longevity of the Neanderthals. By being able to adjust to extreme daylight hours, the species was able to survive in difficult conditions and thrive in its environment.

The study is part of ongoing research into Neanderthal adaptation to the regions in which they lived. It is hoped that further research will help us to better understand the species and their evolution. It may even give us greater insight into our own evolution, allowing us to further understand why we have the differences we do with our own species.