The secret ingredient for fossil preservation at a well-known French web site wouldn’t be present in a Julia Child cookbook. It was a sticky goo made by microalgae, researchers recommend.

An evaluation of roughly 22-million-year-old spider fossils from a fossil-rich rock formation in Aix-en-Provence, France, reveals that the arachnids’ our bodies have been coated with a tarry black substance. That substance, a type of biopolymer, was in all probability secreted by tiny algae referred to as diatoms that lived within the lake or lagoon waters on the historical web site, scientists report April 21 in Communications Earth & Environment.

The biopolymer didn’t simply coat the spiders’ our bodies — it pickled them. By chemically reacting with the spiders’ carbon-rich exoskeletons, the goo helped protect the our bodies from decomposition, permitting them to extra simply turn into fossils, the group hypothesizes.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the most recent Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Thank you for signing up!

There was an issue signing you up.

A clue that this coating may play a task in fossilization got here when the researchers, on a whim, positioned a spider fossil below a fluorescence microscope. To their shock, the substance glowed a vivid yellow-orange. “It was amazing!” says geologist Alison Olcott of the University of Kansas in Lawrence.

The fluorescent imaging painted a vivid, colourful palette onto what was in any other case a reasonably faint spider fossil, Olcott says. In the unique, she may barely inform the spider aside from the background rock. But below fluorescence, she says, the spider fossil glowed in a single shade, the background in one other and the biopolymer in a 3rd.

That discovery — together with an abrupt halt in early 2020 to any further fossil-collecting plans because of the COVID-19 pandemic — swiftly shifted the main focus of the group’s work. “Had it been normal times, this would have been a side note in a taxonomy study” classifying historical spiders, Olcott says. Instead, “I really had to explore what I had,” she provides. “It was me and these images.”

The researchers subsequent sought to establish the chemical make-up of the mysterious substance. The orange-yellow glow, the group discovered, comes from ample carbon and sulfur within the coating. “That got me thinking about sulfurization,” Olcott says.

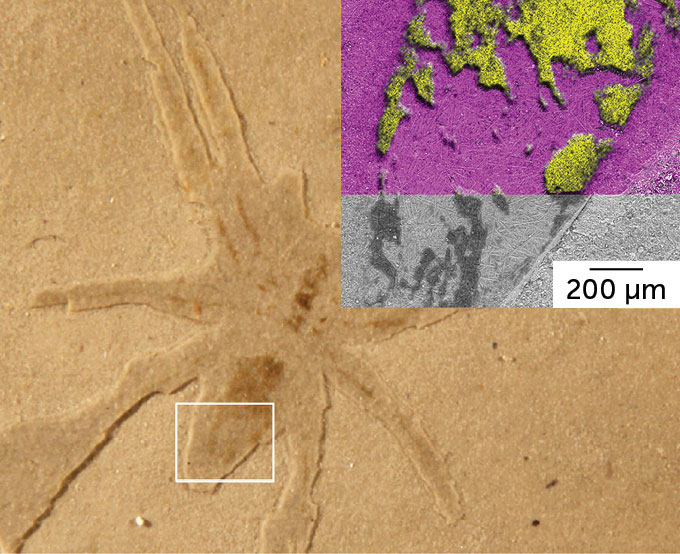

Under seen mild, this fossil of a roughly 22-million-year-old spider seems as a faint impression within the rock. Using scanning electron microscopy, researchers spied a tarry black substance coating elements of the spider (seen within the physique close-up at heart proper). When considered with fluorescence imaging (prime proper), totally different elements within the fossil stand out in vivid shade, primarily based on their chemistry. Here, the sulfur-rich coating seems yellow, whereas the silicon-rich background seems pink.A. OlcottUnder seen mild, this fossil of a roughly 22-million-year-old spider seems as a faint impression within the rock. Using scanning electron microscopy, researchers spied a tarry black substance coating elements of the spider (seen within the physique close-up at heart proper). When considered with fluorescence imaging (prime proper), totally different elements within the fossil stand out in vivid shade, primarily based on their chemistry. Here, the sulfur-rich coating seems yellow, whereas the silicon-rich background seems pink.A. Olcott

Under seen mild, this fossil of a roughly 22-million-year-old spider seems as a faint impression within the rock. Using scanning electron microscopy, researchers spied a tarry black substance coating elements of the spider (seen within the physique close-up at heart proper). When considered with fluorescence imaging (prime proper), totally different elements within the fossil stand out in vivid shade, primarily based on their chemistry. Here, the sulfur-rich coating seems yellow, whereas the silicon-rich background seems pink.A. OlcottUnder seen mild, this fossil of a roughly 22-million-year-old spider seems as a faint impression within the rock. Using scanning electron microscopy, researchers spied a tarry black substance coating elements of the spider (seen within the physique close-up at heart proper). When considered with fluorescence imaging (prime proper), totally different elements within the fossil stand out in vivid shade, primarily based on their chemistry. Here, the sulfur-rich coating seems yellow, whereas the silicon-rich background seems pink.A. Olcott

Sulfurization is the response of natural carbon with sulfur, which types sturdy chemical bonds with the carbon, making it extra immune to degradation and breakdown — much like how tire producers harden rubber to make it extra sturdy. The course of requires a prepared provide of sulfur out there for bonding.

In trendy instances, such a provide comes from the sulfur-rich gooey secretions of diatoms, microalgae discovered floating in lots of waters around the globe. When these secretions meet carbon-laden marine particles headed for the underside of the ocean, this sulfurization course of helps lock the carbon in place and probably preserve it buried within the seafloor.

Similarly, sulfurization may assist to protect delicate carbon-rich fossils, serving to them to resist the check of thousands and thousands of years of geologic time, Olcott says. Scientists have typically famous diatoms within the fossil-bearing rock formations of Aix-en-Provence, in addition to at many comparable fossil-rich websites, she provides. “Everyone’s seeing diatoms everywhere. Thinking about that and the chemistry, I was like, ‘Wait a minute. All the pieces are here to make this chemistry happen.’”

The arachnids’ preservation might need gone like this: A lifeless spider, floating within the water column, grew to become coated within the diatoms’ sticky goo. The goo chemically reacted with the spider’s chitin exoskeleton, kind of pickling it and protecting the exoskeleton largely intact and prepared for fossilization.

That state of affairs “makes sense based on what we know about organic sulfur cycling in modern environments so far,” says Morgan Raven, an natural geochemist on the University of California, Santa Barbara. Scientists nonetheless have lots to study in regards to the situations that enable supplies like chitin to sulfurize, Raven says. “But this study highlights why that matters.”

For instance, if sulfurization selectively helps protect some forms of natural matter — reminiscent of soft-bodied fossils — that “could be a crucial filter on our fossil record, influencing what we do and don’t know about plant and animal evolution,” she provides.

This means of diatom-assisted sulfurization could have been at work in different fossil-rich websites throughout the Cenozoic Era, Olcott says. That span of time started 66 million years in the past, after an asteroid ended the Age of Dinosaurs, and continues to the current day. Before that period, diatoms weren’t widespread. That didn’t occur till silica-bearing grasses sprouted around the globe throughout the Cenozoic, providing a prepared supply of silica for the tiny creatures to construct their delicate our bodies (SN: 5/1/19).

It’s unknown if different biopolymer-producing algae might need helped fossilize soft-bodied creatures from even earlier, reminiscent of throughout the flourishing of Cambrian Period life-forms starting round 541 million years in the past, Olcott says (SN: 4/24/19). “But it would be really interesting to expand this further out.”