It may be simpler for dinosaurs to “mummify” than scientists thought.

Unhealed chunk marks on fossilized dinosaur pores and skin recommend that the animal’s carcass was scavenged earlier than being lined in sediment, researchers report October 12 in PLOS ONE. The discovering challenges the standard view that burial very quickly after demise is required for dinosaur “mummies” to naturally type.

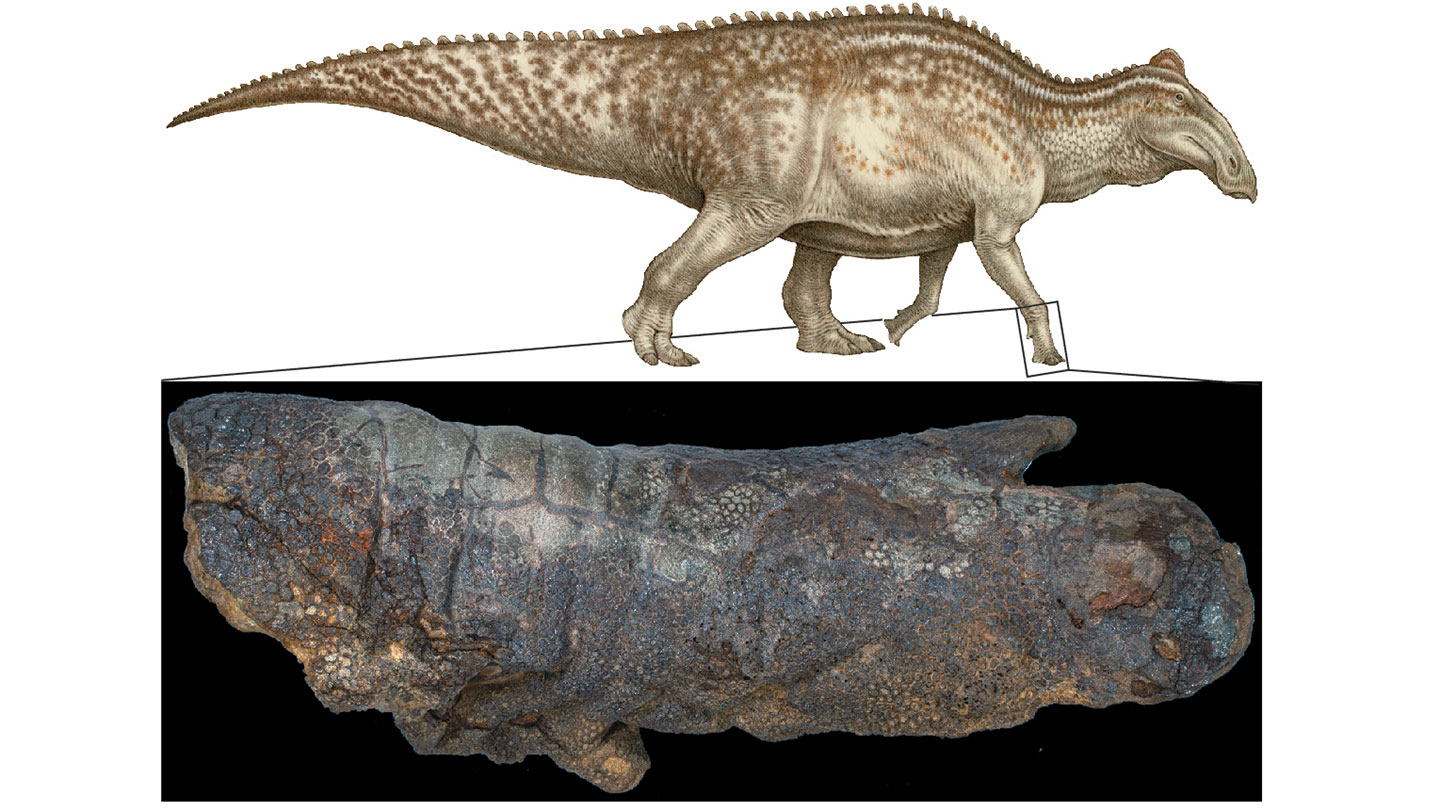

The new analysis facilities on Dakota, an Edmontosaurus fossil unearthed in North Dakota in 1999. About 67 million years in the past, Dakota was a roughly 12-meter-long, duck-billed dinosaur that ate crops. Today, Dakota’s fossilized limbs and tail nonetheless comprise giant areas of well-preserved, fossilized scaly pores and skin, a placing instance of dinosaur “mummification.”

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the most recent Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Thank you for signing up!

There was an issue signing you up.

The creature isn’t a real mummy as a result of its pores and skin has become rock, relatively than being preserved as precise pores and skin. Researchers have come to seek advice from such fossils with exquisitely preserved pores and skin and different delicate tissues as mummies.

In 2018, paleontologist Clint Boyd of the North Dakota Geological Survey in Bismarck and colleagues started a brand new section of cleansing up and inspecting the dinosaur fossil. The staff had discovered what seemed like tears within the tail pores and skin and puncture holes on the animal’s proper entrance foot. To examine what could have brought about the pores and skin marks, the researchers teamed up with Stephanie Drumheller, a paleontologist on the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, to take away additional rocky materials across the marks.

The holes within the pores and skin — significantly these on the entrance limb — are a detailed match for chunk wounds from prehistoric family members of modern-day crocodiles, the researchers say. “This is the first time that’s been seen in dinosaurian soft tissues,” Drumheller says.

Because the marks on the tail are bigger than these on the entrance limb, the staff thinks that at the least two carnivores munched on the Edmontosaurus carcass, most likely as scavengers as a result of the injuries didn’t heal. But scavenging doesn’t match into the standard view of mummification.

“This assumption of rapid burial has been baked into the explanation for mummies for a while,” Drumheller says. That clearly wasn’t the case for Dakota. If scavengers had sufficient time to snack on its physique, then the deceased dino had been out within the open for some time.

Observing Dakota’s deflated pores and skin envelope, shrink-wrapped to the underlying bone with no muscle or different organs, Drumheller had an sudden “eureka moment,” she says. “I had seen something like this before. It just wasn’t in the paleontological literature. It was in the forensics literature.”

When some smaller fashionable scavengers like raccoons feed on the inner organs of a bigger carcass, the scavengers rip open the carcass’s physique. The forensics analysis confirmed that this gap offers any gasses and fluids from additional decomposition an escape route, permitting the remaining pores and skin to dry out. Burial may occur afterward.

The researchers “make a very good point,” says Raymond Rogers, a researcher at Macalester College in Saint Paul, Minn., who research how organisms decay and fossilize and wasn’t concerned within the analysis. “It would be very unlikely for a carcass to achieve advanced stages of desiccation and also experience rapid burial. These two generally presumed prerequisites for mummification seem to be somewhat incompatible.”

Fossilization of soppy tissues — like pores and skin or brains or fleshy head combs — is rare, however not exceptional (SN: 8/20/21; SN: 12/12/13). “If [soft tissue] requires some spectacular confluence of weird events to get it fossilized at all, it’s far more common than then you would expect if that was the case,” Drumheller says. Perhaps, then, mummies originating from frequent carcass fates may clarify this.

But whereas dry, “jerkylike” pores and skin may survive lengthy sufficient to be buried, the circumstances concerned aren’t essentially frequent, says Evan Thomas Saitta, a paleontologist on the University of Chicago who was not concerned with the examine.

“I still suspect that this actual process is a very precise sequence of events, where if you get the timing wrong, you end up without a mummy dinosaur,” he says.

Understanding that sequence of occasions, and simply how frequent it’s, requires determining how fossilization proceeds after a mummy’s burial. This is an space of analysis that Boyd says he’s fascinated by trying into subsequent.

“Is it just the same fossilization process as for the bones?” he asks. “Or do we also need a different set of geochemical conditions to then fossilize the skin?”