It could also be too quickly to mourn the demise of a room-temperature superconductivity declare.

On September 26, the journal Nature retracted a paper describing a fabric that appeared to show right into a superconductor at a comfortable 15° Celsius (SN: 10/14/20). The discover rattled many individuals within the discipline. But a brand new experiment carried out simply days after the retraction helps the world-record temperature declare, say an eyewitness and others accustomed to the experiment.

Superconductors carry electrical energy with no resistance, which suggests they’re helpful for effectively transmitting vitality. They may save monumental quantities of vitality that’s wasted in standard metallic wires. Currently they’re used to create highly effective magnetic fields for medical imaging and particle physics experiments, in addition to serving as parts in high-performance circuity and even levitating high-speed trains. But to work, superconducting supplies usually have to be cooled far beneath 0° C, and lots of to temperatures near absolute zero, or -273° C.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the newest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Thank you for signing up!

There was an issue signing you up.

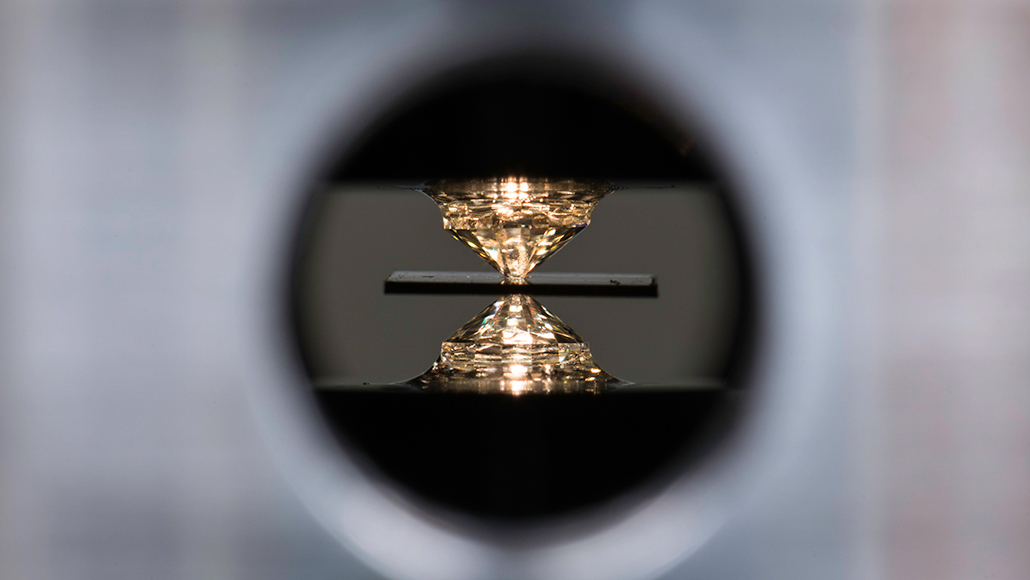

When researchers introduced in 2020 {that a} pattern made from hydrogen, sulfur and a little bit of carbon turned a superconductor at record-shattering temperatures, desires of room-temperature superconducting gave the impression to be on the verge of coming true. One hitch was that the fabric needed to be beneath monumental pressures, about 2.6 million occasions atmospheric pressures — roughly the strain present in elements of Earth’s core. Still, the invention hailed a possible scientific and technological revolution.

In the 2 years since, controversy has swirled across the report. The maelstrom is centered on the best way the researchers ready and processed knowledge that confirmed adjustments in a magnetic property often known as susceptibility. Ultimately, editors at Nature took the bizarre step of retracting the paper regardless of the researchers’ objections. “We have now established that some key data processing steps … used a non-standard, user-defined procedure,” write the editors at Nature within the retraction. “The details of the procedure were not specified in the paper and the validity of the background subtraction has subsequently been called into question.”

The new experiment isn’t a reproduction of the one reported within the retracted paper, however the researchers replicated a portion of their analysis that raised pink flags within the scientific neighborhood.

Ranga Dias, a physicist on the University of Rochester who headed the analysis on the now-retracted paper, led the brand new measurements at Argonne National Laboratory’s Advanced Photon Source in Lemont, Ill. “We have been working on this experiment for almost six months, building and reconfirming the correct methodology,” Dias says. “I would say the data we obtained at Argonne is more compelling, not just comparable,” to the information within the retracted Nature paper.

“The experiment took place over two days, September 27 and 28,” says physicist Nilesh Salke of the University of Illinois Chicago, who was not affiliated with the unique analysis. Salke’s position at Argonne concerned probing a pattern of the fabric in query with X-rays whereas it was exhibiting magnetic susceptibility related to high-temperature superconductivity. “We saw the first susceptibility signal on September 27, consistent with the claims reported in the retracted Nature paper.”

This newest twist is unlikely to place an finish to the controversy that got here with the preliminary declare, at the least within the thoughts of physicist Jorge Hirsch of the University of California, San Diego. Hirsch has been probably the most vocal critics of the room-temperature superconductivity declare.

“I didn’t know it would be retracted, but was hoping it would be retracted,” says Hirsch, who was not affiliated with both the unique or new experiment. He says he requested the authors for the uncooked knowledge from the sooner research one month after it was printed, however he was refused. “The authors said, ‘No we cannot give you the data because our lawyers said that it would affect our patent rights.’”

With intervention from Nature, Hirsch finally bought the numbers. What he noticed disturbed him. Hirsch is skeptical that high-temperature superconductivity is feasible in these kinds of hydrogen-based supplies normally, however says he’s objecting based mostly on the best way the information have been dealt with.

“There were real problems between the raw data and the published data,” Hirsch says. He believes that Nature’s retraction doesn’t go far sufficient. “It’s not that the data were not properly processed.” Along with physicist Dirk van der Marel of the University of Geneva, Hirsch delves into issues with the information in a paper printed September 15 within the International Journal of Modern Physics B. “Our analysis proves mathematically that the raw data were not measured in the laboratory. They were fabricated.”

Dias and colleagues deny any impropriety of their knowledge or evaluation and are transferring ahead with experiments just like the one at Argonne. But that work awaits peer assessment. For now, Nature’s retraction bolsters present doubts round room-temperature superconductivity.

“In the end, all of this has to be validated by different groups getting the answer,” Hirsch says.