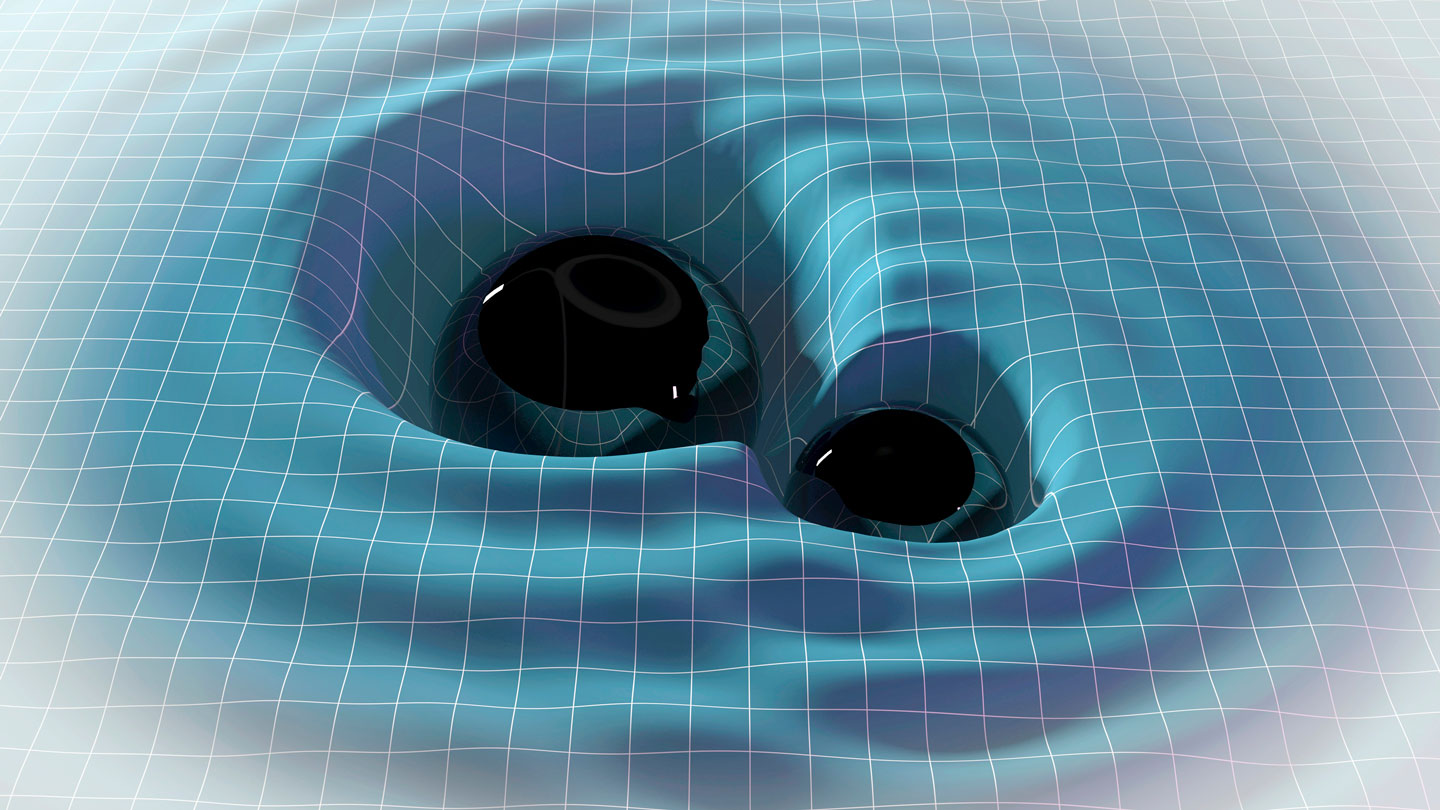

Until recently, gravitational waves could have been a figment of Einstein’s imagination. Before they were detected, these ripples in spacetime existed only in the physicist’s general theory of relativity, as far as scientists knew.

Just as light comes in a spectrum, or a variety of wavelengths, so do gravitational waves. Different wavelengths point to different types of cosmic origins and require different flavors of detectors.

Gravitational waves with wavelengths of a few thousand kilometers — like those detected by LIGO in the United States and its partners Virgo in Italy and KAGRA in Japan — come mostly from merging pairs of black holes 10 or so times the mass of the sun, or from collisions of dense cosmic nuggets called neutron stars (SN: 2/11/16). These detectors could also spot waves from certain types of supernovas — exploding stars — and from rapidly rotating neutron stars called pulsars (SN: 5/6/19).

In contrast, immense ripples that span light-years are thought to be created by orbiting pairs of whopper black holes with masses billions of times that of the sun. In June, scientists reported the first strong evidence for these types of waves by turning the entire galaxy into a detector, watching how the waves tweaked the timing of regular blinks from pulsars scattered throughout the Milky Way (SN: 6/28/23).

2023-09-15 07:00:00

Post from www.sciencenews.org