The fading of a once-vibrant yellow rose reveals how the ravages of time and chemical alteration can dampen the visible energy of a portray.

Most of the flowers in Abraham Mignon’s seventeenth century portray Still Life with Flowers and a Watch appear to leap off the canvas. But one yellow rose, painted with arsenic sulfide–primarily based orpiment pigment, is a flat, jarring factor. That wasn’t Mignon’s intention: The rose misplaced its luster as a result of chemical transformation of a few of its unique brilliant pigment into colorless lead arsenates, researchers report June 8 in Science Advances.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the newest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Thank you for signing up!

There was an issue signing you up.

Paintings conservator Nouchka De Keyser of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and colleagues analyzed the rose utilizing noninvasive methods together with X-ray fluorescence imaging and X-ray powder diffraction (SN: 10/1/21). The crew first mapped the lingering traces of arsenic, lead, calcium and different chemical components within the layers of paint to disclose how Mignon rigorously layered paint to create a virtually three-dimensional rose out of sunshine and shadow.

The analyses additionally revealed two newer crystals on the rose containing each lead and arsenic. Called mimetite and schultenite, the crystals are the product of a sequence of chemical reactions. First, the response of orpiment with mild created a extremely cellular kind of arsenic referred to as arsenolite. That mobilized arsenolite then discovered its option to an underlying layer of lead white paint and chemically reacted with it to provide the mimetite and schultenite. The crystals lack the intense shade of the orpiment — as a substitute, they’re colorless and flatten the flower’s look.

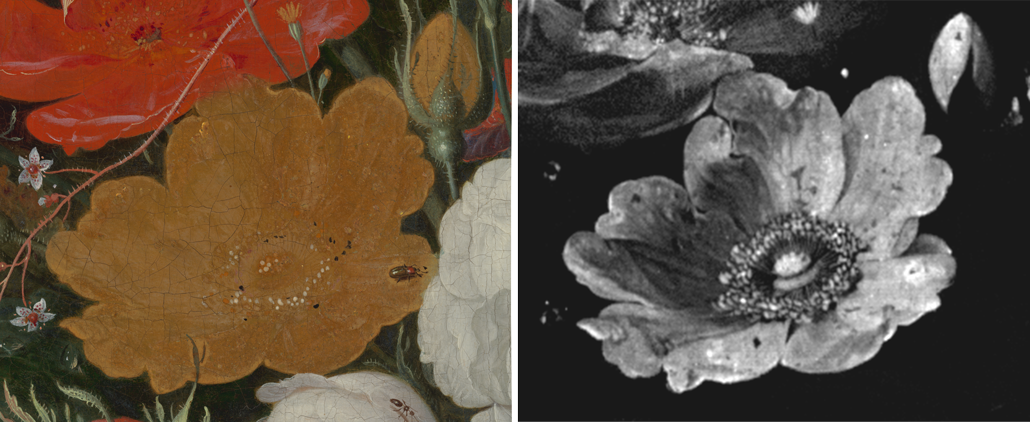

This yellow rose (left) is proven because it seems to the bare eye as we speak within the portray Still Life with Flowers and a Watch. X-ray fluorescence imaging reveals a extra masterful ghost of the previous. The picture (proper) reveals the basic distribution of arsenic that is still within the rose. Originally painted in an arsenic sulfide–primarily based brilliant yellow pigment, chemical reactions with mild and with different paint layers dulled the flower’s look over time.N. De Keyser et al/Science Advances 2022

This yellow rose (left) is proven because it seems to the bare eye as we speak within the portray Still Life with Flowers and a Watch. X-ray fluorescence imaging reveals a extra masterful ghost of the previous. The picture (proper) reveals the basic distribution of arsenic that is still within the rose. Originally painted in an arsenic sulfide–primarily based brilliant yellow pigment, chemical reactions with mild and with different paint layers dulled the flower’s look over time.N. De Keyser et al/Science Advances 2022

Science can’t flip again the clock on the chemical transformation to revive the rose’s erstwhile glory — that’s a one-way road. But digital reconstructions comparable to these within the new examine may supply a number of advantages and never simply to scientists and artwork historians, De Keyser says. Not solely can such reconstructions reveal now-faded components in different work — they could additionally seem in museums, permitting guests a ghostly glimpse of a portray’s true previous.