A single, doomed moon might clear up a few mysteries about Saturn.

This hypothetical lacking moon, dubbed Chrysalis, might have helped tilt Saturn over, researchers counsel September 15 in Science. The ensuing orbital chaos may then have led to the moon’s demise, shredding it to kind the long-lasting rings that encircle the planet right this moment.

“We like it because it’s a scenario that explains two or three different things that were previously not thought to be related,” says research coauthor Jack Wisdom, a planetary scientist at MIT. “The rings are related to the tilt, who would ever have guessed that?”

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the newest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Thank you for signing up!

There was an issue signing you up.

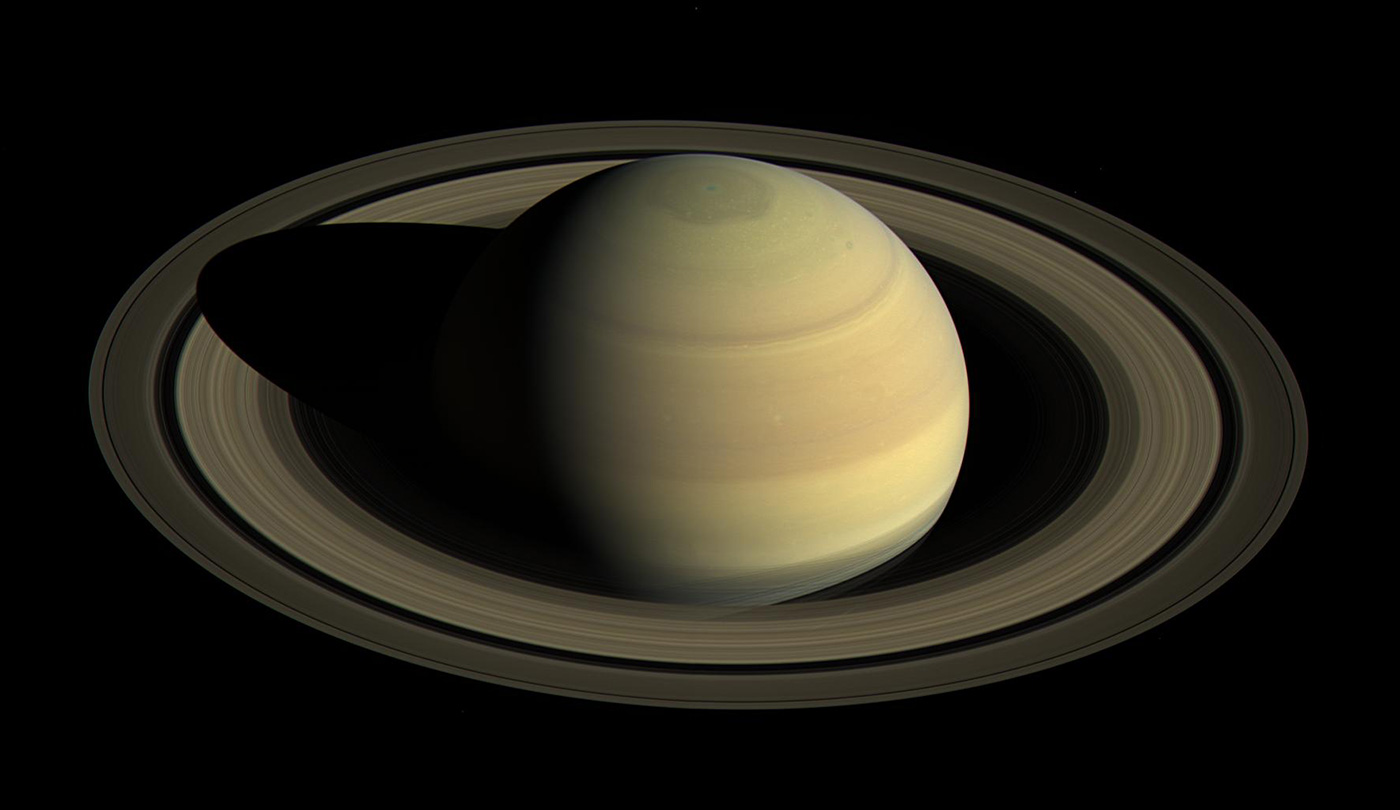

Saturn’s rings seem surprisingly younger, a mere 150 million years or so previous (SN: 12/14/17). If the dinosaurs had telescopes, they could have seen a ringless Saturn. Another mysterious function of the gasoline large is its practically 27-degree tilt relative to its orbit across the solar. That tilt is just too giant to have fashioned when Saturn did or to be the results of collisions knocking the planet over.

Planetary scientists have lengthy suspected that the lean is expounded to Neptune, due to a coincidence in timing between the best way the 2 planets transfer. Saturn’s axis wobbles, or precesses, like a spinning high. Neptune’s whole orbit across the solar additionally wobbles, like a struggling hula hoop.

The durations of each precessions are virtually the identical, a phenomenon often called resonance. Scientists theorized that gravity from Saturn’s moons — particularly the most important moon, Titan — helped the planetary precessions line up. But some options of Saturn’s inside construction weren’t recognized properly sufficient to show that the 2 timings had been associated.

Wisdom and colleagues used precision measurements of Saturn’s gravitational area from the Cassini spacecraft, which plunged into Saturn in 2017 after 13 years orbiting the gasoline large, to determine the small print of its inside construction (SN: 9/15/17). Specifically, the group labored out Saturn’s second of inertia, a measure of how a lot pressure is required to tip the planet over. The group discovered that the second of inertia is near, however not precisely, what it will be if Saturn’s spin had been in excellent resonance with Neptune’s orbit.

“We argue that it’s so close, it couldn’t have occurred by chance,” Wisdom says. “That’s where this satellite Chrysalis came in.”

After contemplating a volley of different explanations, Wisdom and colleagues realized that one other smallish moon would have helped Titan convey Saturn and Neptune into resonance by including its personal gravitational tugs. Titan drifted away from Saturn till its orbit synced up with that of Chrysalis. The enhanced gravitational kicks from the bigger moon despatched the doomed smaller moon on a chaotic dance. Eventually, Chrysalis swooped so near Saturn that it grazed the enormous planet’s cloud tops. Saturn ripped the moon aside, and slowly floor its items down into the rings.

Calculations and laptop simulations confirmed that the state of affairs works, although not on a regular basis. Out of 390 simulated eventualities, solely 17 ended with Chrysalis disintegrating to create the rings. Then once more, huge, hanging rings like Saturn’s are uncommon, too.

The title Chrysalis got here from that spectacular ending: “A chrysalis is a cocoon of a butterfly,” Wisdom says. “The satellite Chrysalis was dormant for 4.5 billion years, presumably. Then suddenly the rings of Saturn emerged from it.”

The story hangs collectively, says planetary scientist Larry Esposito of the University of Colorado Boulder, who was not concerned within the new work. But he’s not totally satisfied. “I think it’s all plausible, but maybe not so likely,” he says. “If Sherlock Holmes is solving a case, even the improbable explanation may be the right one. But I don’t think we’re there yet.”