Some micro organism carry tiny syringes crammed with chemical substances that will skinny out rivals or incapacitate predators. Now, researchers have gotten up-close views of those syringes, technically generally known as contractile injection methods, from a sort of cyanobacteria and a marine bacterium.

Figuring out how key components of the molecular syringes work could assist scientists devise their very own nanomachines. Artificial injection machines may direct antibiotics in opposition to troublesome micro organism whereas leaving pleasant microbes untouched.

Genes encoding items of the injection equipment are discovered in lots of bacterial species. But, “just by looking at the genes, it’s quite hard to predict how these contractile injection systems work,” says Gregor Weiss, a mobile structural biologist at ETH Zurich.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the newest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Thank you for signing up!

There was an issue signing you up.

So Weiss and colleagues examined bacterial syringes utilizing cryo-electron microscopy, wherein cells are flash frozen to seize mobile constructions as they usually look in nature (SN: 6/22/17).

Previously, researchers have discovered syringes anchored in some micro organism’s outer membranes, the place the micro organism can shoot their payload into cells they stumble upon. Other species’ injectors squirt their contents into the setting.

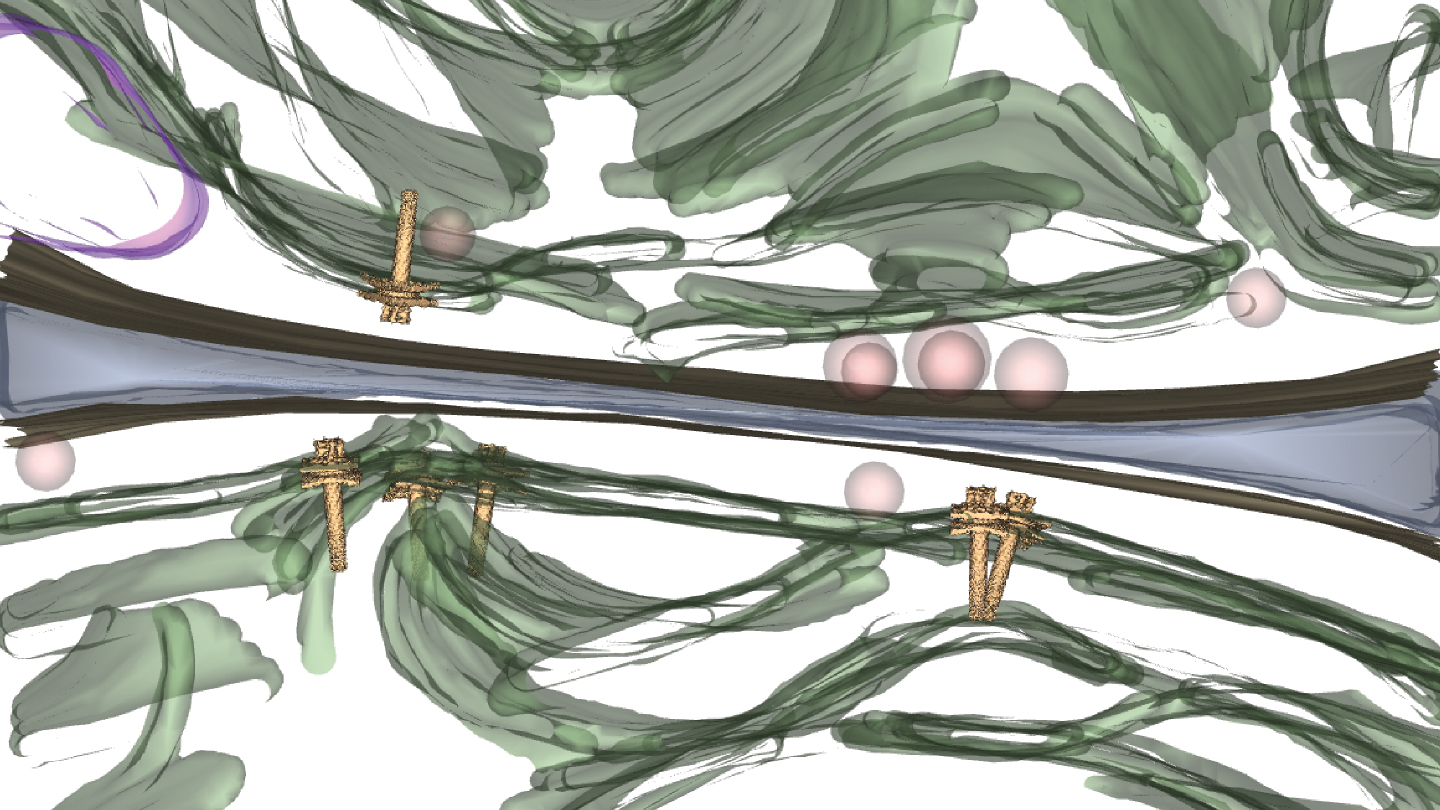

But in a sort of cyanobacteria known as Anabaena, the syringes are in an uncommon place, nestled within the membrane of the interior construction the place the micro organism perform photosynthesis, Weiss and colleagues report within the March Nature Microbiology. Buried contained in the cells, “it’s hard to imagine how [the syringes] could get out and interact with the target organism,” Weiss says.

Anabaena could use its syringes in opposition to itself to set off programmed cell dying when the cyanobacteria come beneath stress. In the group’s experiments, ultraviolet gentle or excessive salt ranges in water triggered some syringes to dump their payload. That led to the dying of some Anabaena cells within the lengthy chains that the cyanobacteria develop in, forming hole “ghost cells.”

Ghost cells shed their outer wall and membrane, exposing unfired syringes within the interior membrane to the surface. The ghosts could act like Trojan horses, delivering their lethal payload to predators or rivals, the group hypothesizes. The researchers haven’t but discovered which organisms are the possible targets of Anabaena’s syringes.

Inside a sort of marine micro organism known as Algoriphagus machipongonensis, the story is a bit totally different. Here, the syringes have a distinct structure and float unmoored inside the bacterial cell, ETH Zurich’s Charles Ericson and colleagues report within the March Nature Microbiology. The injectors are additionally discovered within the liquid wherein the micro organism are grown within the laboratory, however how they get out of the cell is a thriller. Perhaps they’re launched when the micro organism die or get eaten by a predator, Ericson says.

The group additionally discovered two proteins loaded contained in the Algoriphagus’ syringes, however what these proteins do isn’t recognized. The researchers tried genetically engineering E. coli to provide one of many proteins, however it kills the micro organism, says examine coauthor Jingwei Xu, additionally at ETH Zurich.

Comparing the constructions of syringes from numerous species, the researchers recognized sure constructions inside the machines which might be related, however barely totally different from species to species. Learning how these modifications change the best way the injectors work could enable researchers to load totally different cargoes into the tubes or goal the syringes in opposition to particular micro organism or different organisms. “Now we have the general blueprint,” Ericson says, “can we re-engineer it?”