Good information for late bloomers: Planets might have hundreds of thousands of years extra time to come up round most stars than beforehand thought.

Planet-making disks round younger stars usually final for five million to 10 million years, researchers report in a research posted October 6 at arXiv.org. That disk lifetime, based mostly on a survey of close by younger star clusters, is an effective deal longer than the earlier estimate of 1 million to three million years.

“One to three megayears is a really strong constraint for forming planets,” says astrophysicist Susanne Pfalzner of Forschungszentrum Jülich in Germany. “Finding that we have a lot of time just relaxes everything” for constructing planets round younger stars.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the newest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Thank you for signing up!

There was an issue signing you up.

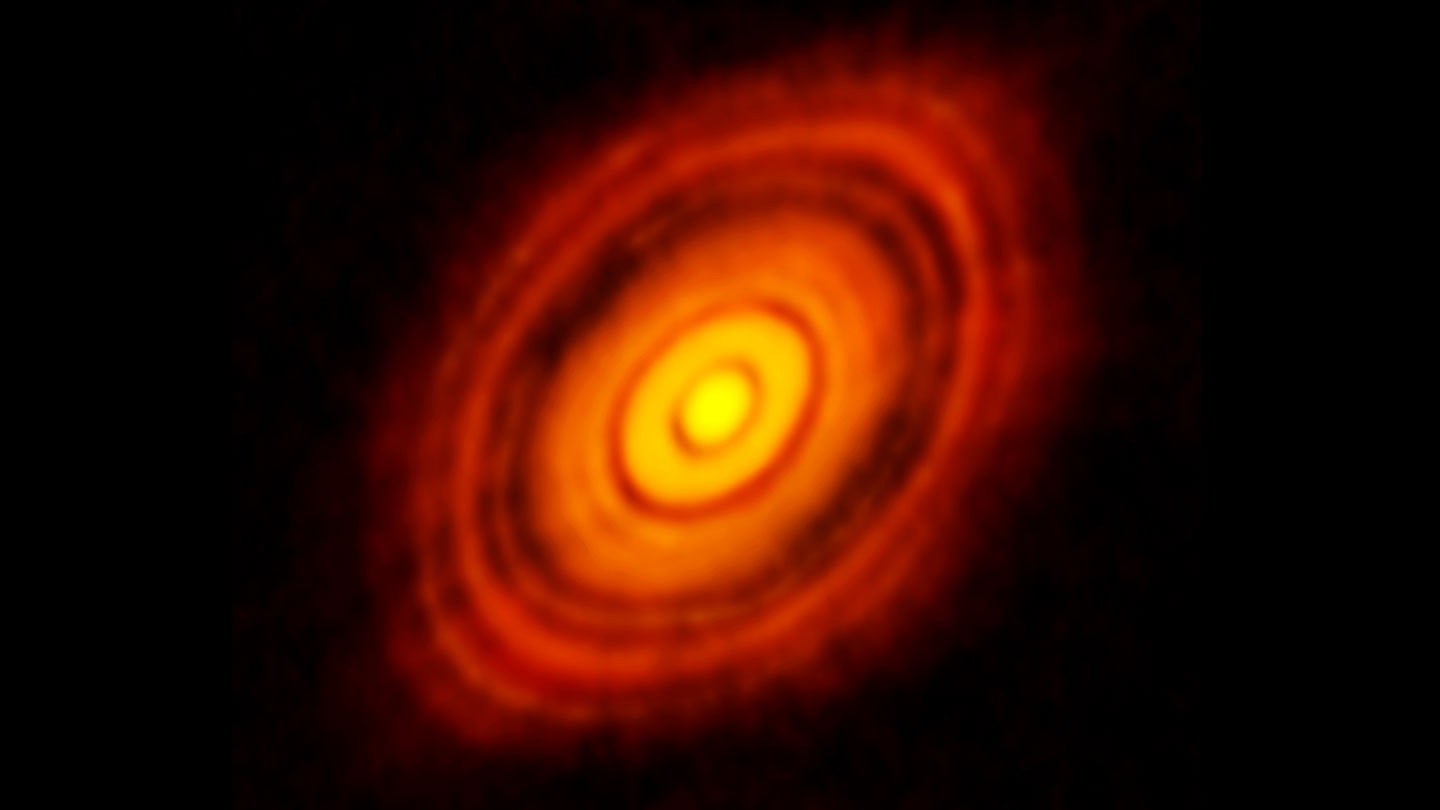

Planets massive and small develop within the disks of gasoline and dirt that swirl round younger stars (SN: 5/20/20). Once a disk vanishes, it’s too late to make any extra new worlds.

Past research have estimated disk lifetimes by trying on the fraction of younger stars of various ages that also have disks — specifically, by observing star clusters with identified ages. But Pfalzner and her colleagues found one thing odd: The farther a star cluster is from Earth, the shorter the estimated disk lifetime. That made no sense, she says, as a result of why ought to the lifetime of a protoplanetary disk depend upon how far it’s from us?

The reply is kind of easy: It doesn’t. But in clusters which are farther away, it’s more durable to see most stars. “When you look at larger distances, you see higher-mass stars,” Pfalzner says, as a result of these stars are brighter and simpler to see. “You basically don’t see the low-mass stars.” But the lowest-mass stars represent the overwhelming majority. These stars, orange and crimson dwarfs, are cooler, smaller and fainter than the solar.

So Pfalzner and her colleagues examined solely the closest younger star clusters, these inside 650 light-years of Earth, and located that the fraction of stars with planet-making disks was a lot larger than that reported in earlier research. This evaluation confirmed that “the low-mass stars have much longer disk lifetimes, between 5 and 10 megayears,” than astronomers realized, she says. In distinction, disks round higher-mass stars are identified to disperse quicker than this, maybe as a result of their suns’ brighter gentle pushes the gasoline and dirt away extra rapidly.

“I wouldn’t say that this is definite proof” for such lengthy disk lifetimes round orange and crimson dwarfs, says Álvaro Ribas, an astronomer on the University of Cambridge who was not concerned with the work. “But it’s quite convincing.”

To bolster the end result, he’d wish to see observations of extra distant star clusters — maybe with the James Webb Space Telescope — to find out the fraction of the faintest stars which have preserved their planet-making disks between 5 million and 20 million years (SN: 10/11/22).

If the disks across the lowest mass stars do certainly have lengthy lifetimes, that will clarify a distinction between our photo voltaic system and people of most crimson dwarfs, Pfalzner says. The latter typically lack gasoline giants like Jupiter and Saturn, that are about 10 instances the diameter of Earth. Instead, these stars steadily have quite a few ice giants like Uranus and Neptune, about 4 instances the diameter of Earth. Perhaps Neptune-sized planets come up in bigger numbers when a planet-making disk lasts longer, Pfalzner says, accounting for why these worlds are likely to abound round smaller stars.