“Follow the water” has lengthy been the mantra of scientists trying to find life past Earth. After all, the one identified cradle of life within the cosmos is the watery planet we name dwelling. But now there’s extra proof suggesting {that a} potential discovery of liquid water on Mars won’t be so watertight, researchers report September 26 in Nature Astronomy.

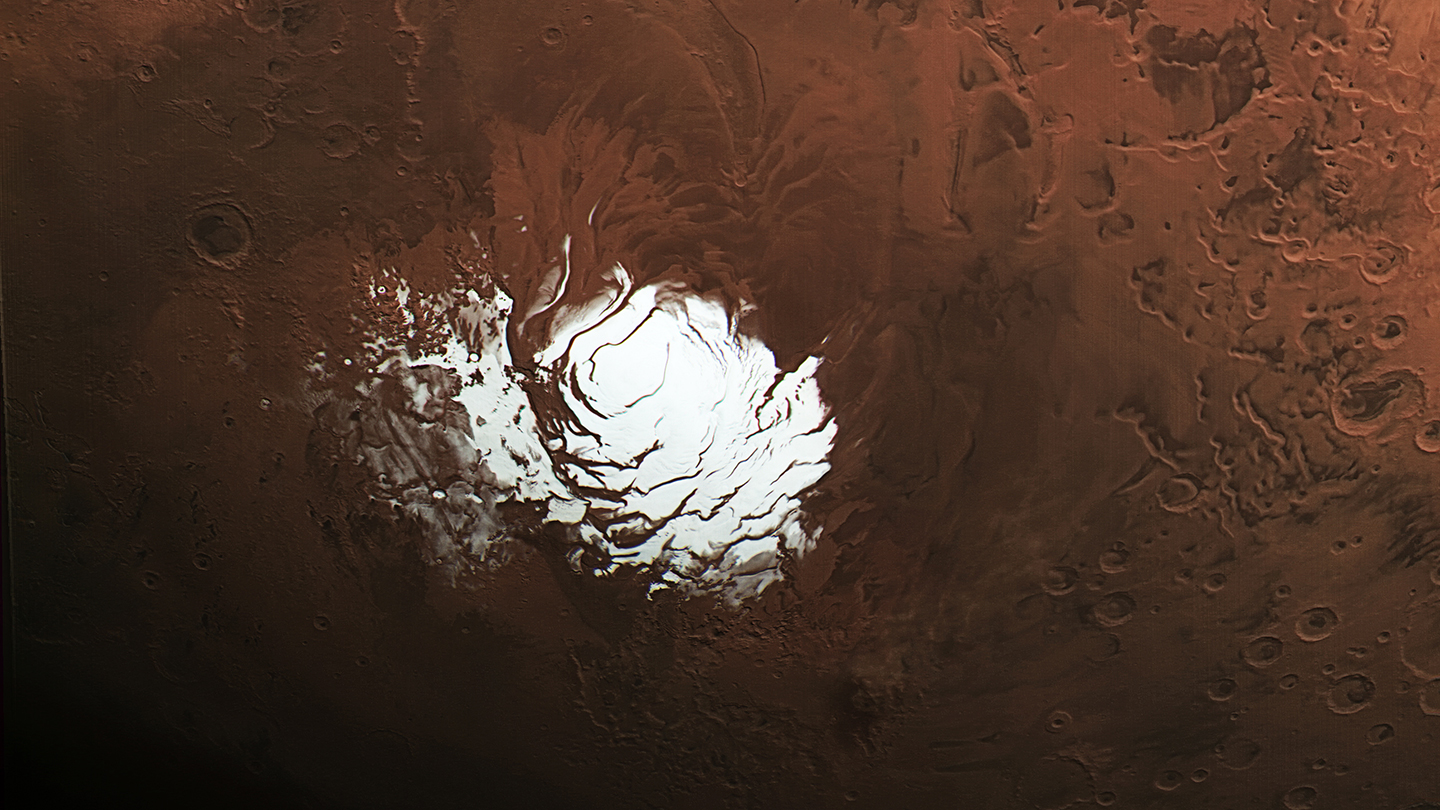

In 2018, scientists introduced the invention of a giant subsurface lake close to Mars’ south pole (SN: 7/25/18). That declare — and follow-up observations suggesting extra buried swimming pools of liquid water on the Red Planet (SN: 9/28/20) — fueled pleasure about lastly discovering an extraterrestrial world probably conducive to life.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the most recent Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Thank you for signing up!

There was an issue signing you up.

But researchers have since proposed that these discoveries won’t maintain as much as scrutiny. In 2021, one group instructed that clay minerals and frozen brines, fairly than liquid water, is likely to be accountable for the robust radar indicators that researchers noticed (SN: 7/16/21). Spacecraft orbiting Mars beam radio waves towards the Red Planet and measure the timing and depth of the mirrored waves to deduce what’s beneath the Martian floor.

And now one other workforce has proven that extraordinary layers of rock and ice can produce lots of the identical radar indicators beforehand attributed to water. Planetary scientist Dan Lalich of Cornell University and his colleagues calculated how flat layers of bedrock, water ice and carbon dioxide ice — all identified to be plentiful on Mars — mirror radio waves. “It was a pretty simple analysis,” Lalich says.

The researchers discovered that they might reproduce among the anomalously robust radar indicators considered resulting from liquid water. Individual radar indicators from totally different layers of rock and ice add collectively when the layers are a sure thickness, Lalich says. That produces a stronger sign, which is then picked up by a spacecraft’s devices. But these devices can’t all the time inform the distinction between a radio wave coming from one layer and one which’s the results of a number of layers, he says. “They look like one reflection to the radar.”

These outcomes don’t rule out liquid water on Mars, Lalich and his colleagues acknowledge. “This is just saying that there are other options,” he says.

The new discovering is “a plausible scenario,” says Aditya Khuller, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University in Tempe who was not concerned within the analysis. But till scientists get much more information from the Red Planet, it’ll be troublesome to know whether or not liquid water really exists on Mars, Khuller says. “It’s important to be open-minded at this point.”