Hunter-gatherer teams dwelling in southwest Asia could have began holding and caring for animals almost 13,000 years in the past — roughly 2,000 years sooner than beforehand thought.

Ancient plant samples extracted from present-day Syria present hints of charred dung, indicating that folks have been burning animal droppings by the top of the Old Stone Age, researchers report September 14 in PLOS One. The findings counsel people have been utilizing the dung as gasoline and should have began animal tending throughout and even earlier than the transition to agriculture. But what animals produced the dung and the precise nature of the animal-human relationship stay unclear.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the most recent Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Thank you for signing up!

There was an issue signing you up.

“We know today that dung fuel is a valuable resource, but it hasn’t really been documented prior to the Neolithic,” says Alexia Smith, an archaeobotanist on the University of Connecticut in Storrs (SN: 8/5/03).

Smith and her colleagues reexamined 43 plant samples taken within the Nineteen Seventies from a residential dwelling at Abu Hureyra, an archaeological web site now misplaced below the Tabqa Dam reservoir. The samples date from roughly 13,300 to 7,800 years in the past, spanning the transition from hunter-gatherer societies to farming and herding.

Throughout the samples, the researchers discovered various quantities of spherulites, tiny crystals that kind within the intestines of animals and are deposited in dung. There was a noticeable uptick between 12,800 and 12,300 years in the past, when darkened spherulites additionally appeared in a hearth pit — proof they have been heated to between 500⁰ and 700⁰ Celsius, and possibly burned.

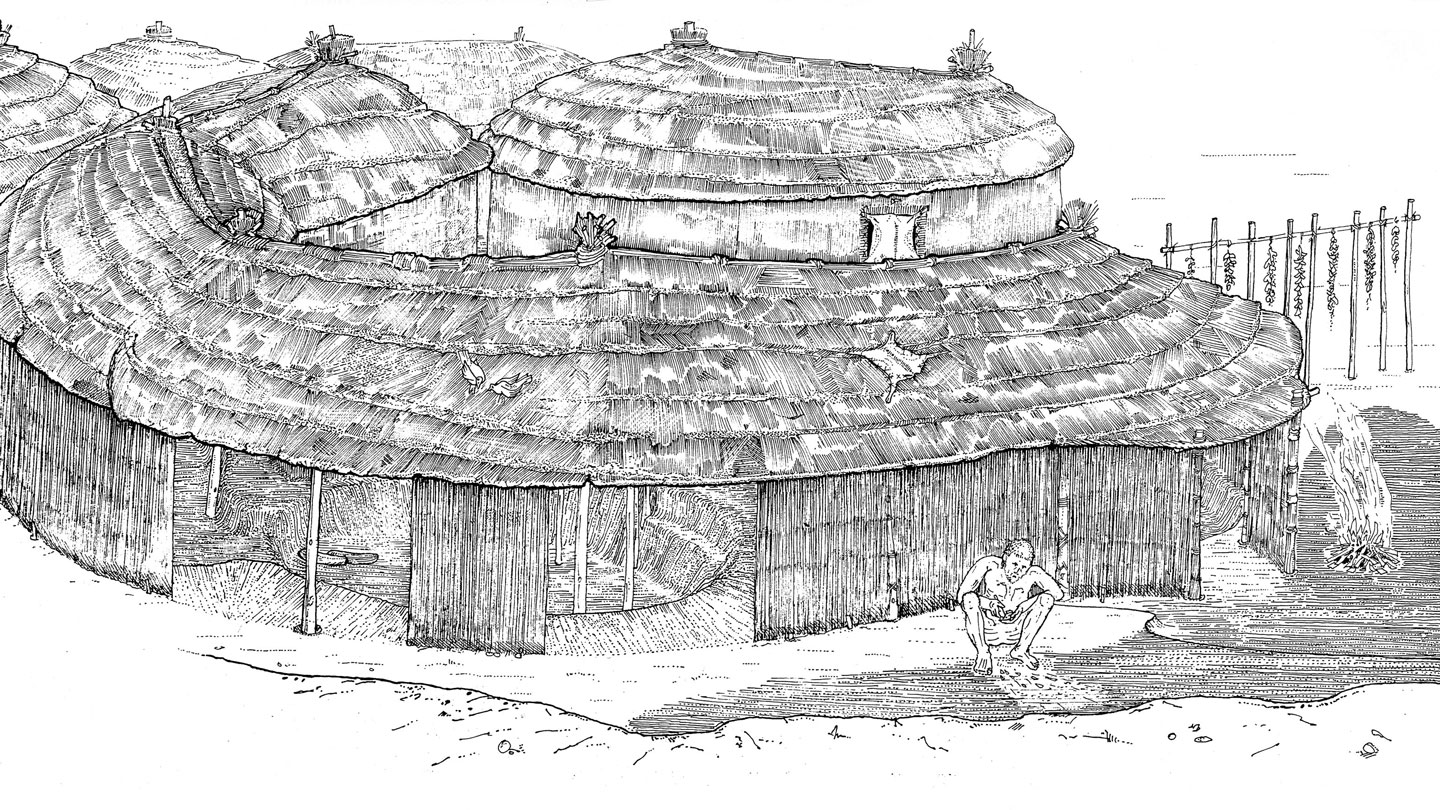

The staff then cross-referenced these findings towards beforehand revealed information from Abu Hureyra. It discovered that the dung burning coincided with a shift from round to linear buildings, a sign of a extra sedentary life-style, together with steadily rising numbers of untamed sheep on the web site and a decline in gazelle and different small recreation. Combined, the authors argue, these findings counsel people could have began tending animals exterior their properties and have been burning the piles of dung at hand as a complement to wooden.

“The spherulite evidence reported here confirms that dung of some sort was used as fuel,” says Naomi Miller, an archaeobotanist on the University of Pennsylvania who was not concerned with the research.

Figuring out what animal left the dung might reveal whether or not animals have been tethered exterior or not. While the authors suggest wild sheep, which might have been extra accommodating to seize, Miller suggests the supply was in all probability roaming wild gazelle.

“Spherulites coming from off-site collection of gazelle dung, stored until burned as fuel, is to my mind a more plausible interpretation,” Miller says. Even if saved for a number of days, she says, sheep wouldn’t produce giant quantities of dung.

“The whole thing is a classic whodunit,” says anthropologist Melinda Zeder, one thing maybe DNA evaluation might clear up (SN: 7/6/17). Gazelle could be the supply, she says, and if captured younger, the animals could have even been tended for some time — even when they weren’t ultimately domesticated.

“The interesting thing is that people [were] experimenting with their environment,” says Zeder, of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. “Domestication is almost incidental to that.”