It sounds just like the setup for a joke: If radio waves provide you with radar and sound provides you sonar, what do gravitational waves get you?

The reply may be “GRADAR” — gravitational wave “radar” — a possible future know-how that would use reflections of gravitational waves to map the unseen universe, say researchers in a paper accepted to Physical Review Letters. By on the lookout for these indicators, scientists could possibly discover darkish matter or dim, unique stars and find out about their deep insides.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the most recent Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Thank you for signing up!

There was an issue signing you up.

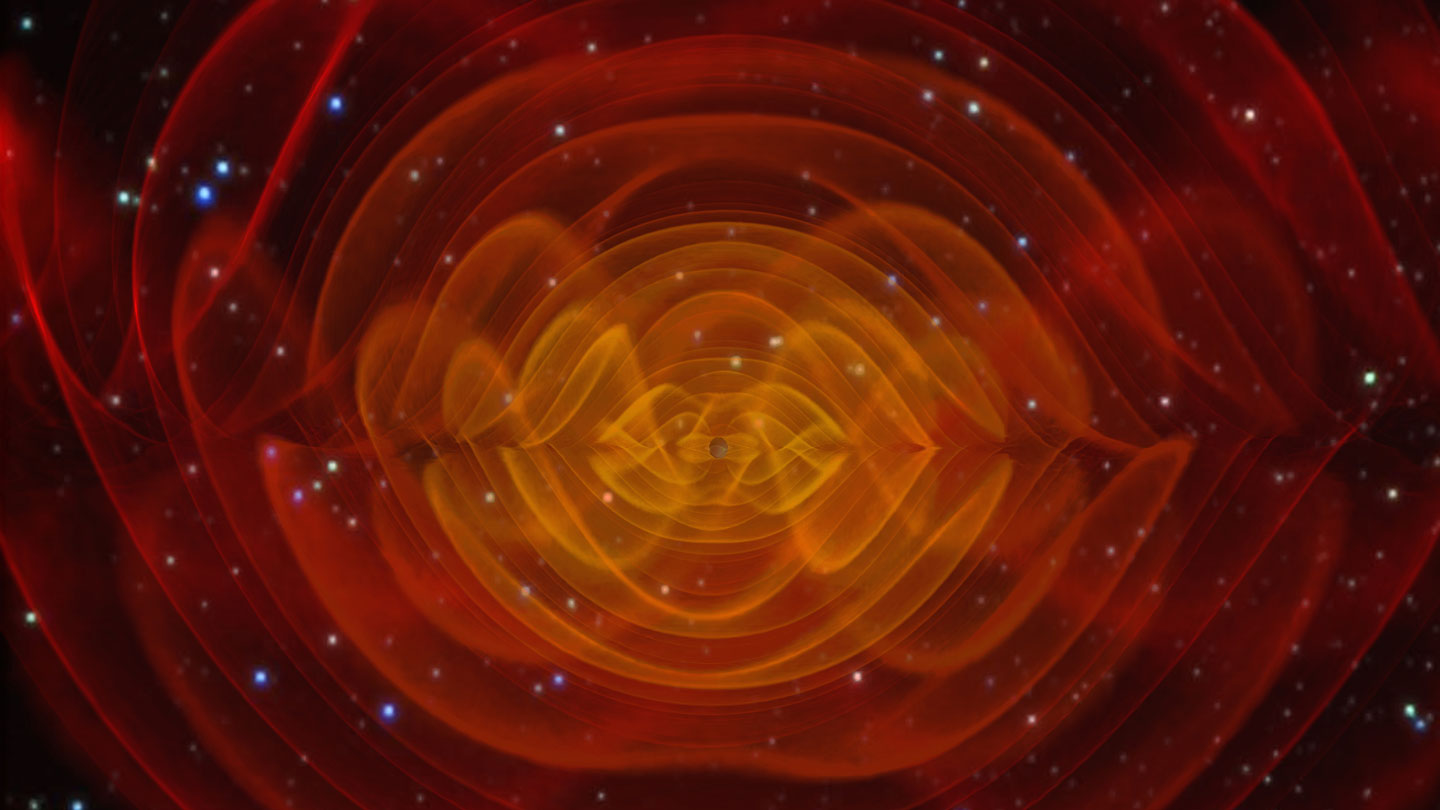

Astronomers routinely use gravitational waves — touring ripples within the material of area and time itself, first detected in 2015 — to observe cataclysmic occasions which are exhausting to check with mild alone, such because the merging of two black holes (SN: 2/11/2016).

But physicists have additionally identified a few seemingly ineffective property of gravitational waves: They can change course. Einstein’s idea of gravity says that spacetime will get warped by matter, and any wave passing by means of these distortions will change course. The upshot is that when one thing emits gravitational waves, a part of the sign comes straight at Earth, however some would possibly arrive later — like an echo — after taking longer paths that bend round a star or the rest heavy.

Scientists have at all times thought these later indicators, known as “gravitational glints,” must be too weak to detect. But physicists Craig Copi and Glenn Starkman of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, took a leap: Working off Einstein’s idea, they calculated how robust the sign could be when waves scatter by means of the gravitational discipline inside a star itself.

“The shocking thing is that you seem to get a much larger result than you would have expected,” Copi says. “It’s something we’re still trying to understand, where that comes from — whether it’s believable, even, because it just seems too good to be true.”

If gravitational glints could be so robust, astronomers may presumably use them to hint the insides of stars, the crew says. Researchers may even search for large our bodies in area that might in any other case be unimaginable to detect, like globs of darkish matter or lone neutron stars on the opposite facet of the observable universe.“That would be a very exciting probe,” says Maya Fishbach, an astrophysicist at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill., who was not concerned within the research.

There are nonetheless causes to be cautious, although. If this phenomenon stands as much as extra detailed scrutiny, Fishbach says, scientists must perceive it higher earlier than they may use it — and that can most likely be troublesome.

“It’s a very hard calculation,” Copi says.

But comparable challenges have been overcome earlier than. “The whole story of gravitational wave detection has been like that,” Fishbach says. It was a battle to do all the maths wanted to know their measurements, she says, however now the sector is taking off (SN: 1/21/21). “This is the time to really be creative with gravitational waves.”