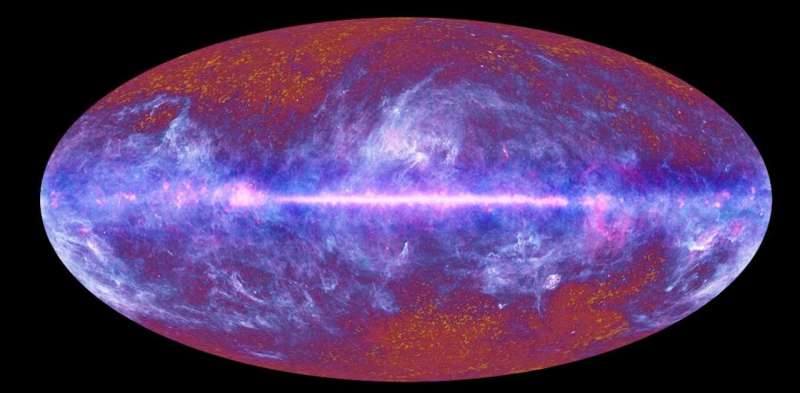

The light left over from the Big Bang, seen by the Planck satellite. Credit: ESA/ LFI & HFI Consortia, CC BY-SA

Interest in the multiverse theory, suggesting that our universe is just one of many, spiked following the release of the movie “Everything Everywhere All At Once.” The film follows Evelyn Wang on her journey to connect with versions of herself in parallel universes to ultimately stop the destruction of the multiverse.

The multiverse idea has long been an inspiration for science fiction writers. But does it have any basis in science? And if so, is it a concept we could ever test experimentally?

That’s the topic of the third episode of our podcast Great Mysteries of Physics—hosted by me, Miriam Frankel, science editor at The Conversation, and supported by FQxI, the Foundational Questions Institute.

“One way to think of a multiverse is just to say, ‘Well, the universe might be really, really big—much bigger than our observable universe—and so there could be other regions of the universe that are far beyond our horizon that have different things happening in them’,” explains Katie Mack, Hawking chair in cosmology and science communication at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Canada. “And I think that idea is totally well accepted in cosmology.”

The idea that there could be other parts of the cosmos with different physical laws, processes and histories is hard to ignore. And the concept is consistent with the theories of quantum mechanics, which governs the micro-world of atoms and particles, string theory (an attempt at a theory of everything)—and also with cosmic inflation, which says the infant universe blew up hugely in size during a brief growth spurt, and then continued to grow at a less frantic pace. These theories each give rise to their own version of the multiverse theory.

For Andrew Pontzen, a professor of cosmology at University College London in the UK, quantum mechanics is the best reason to believe in the multiverse. According to quantum mechanics, particles can be in a mix of different possible states, such as locations, which is known as a “superposition”. But when we measure them, the superposition breaks and each particle randomly “picks” one state.

2023-03-28 06:00:04

Article from phys.org