Even sperm gotta stick collectively.

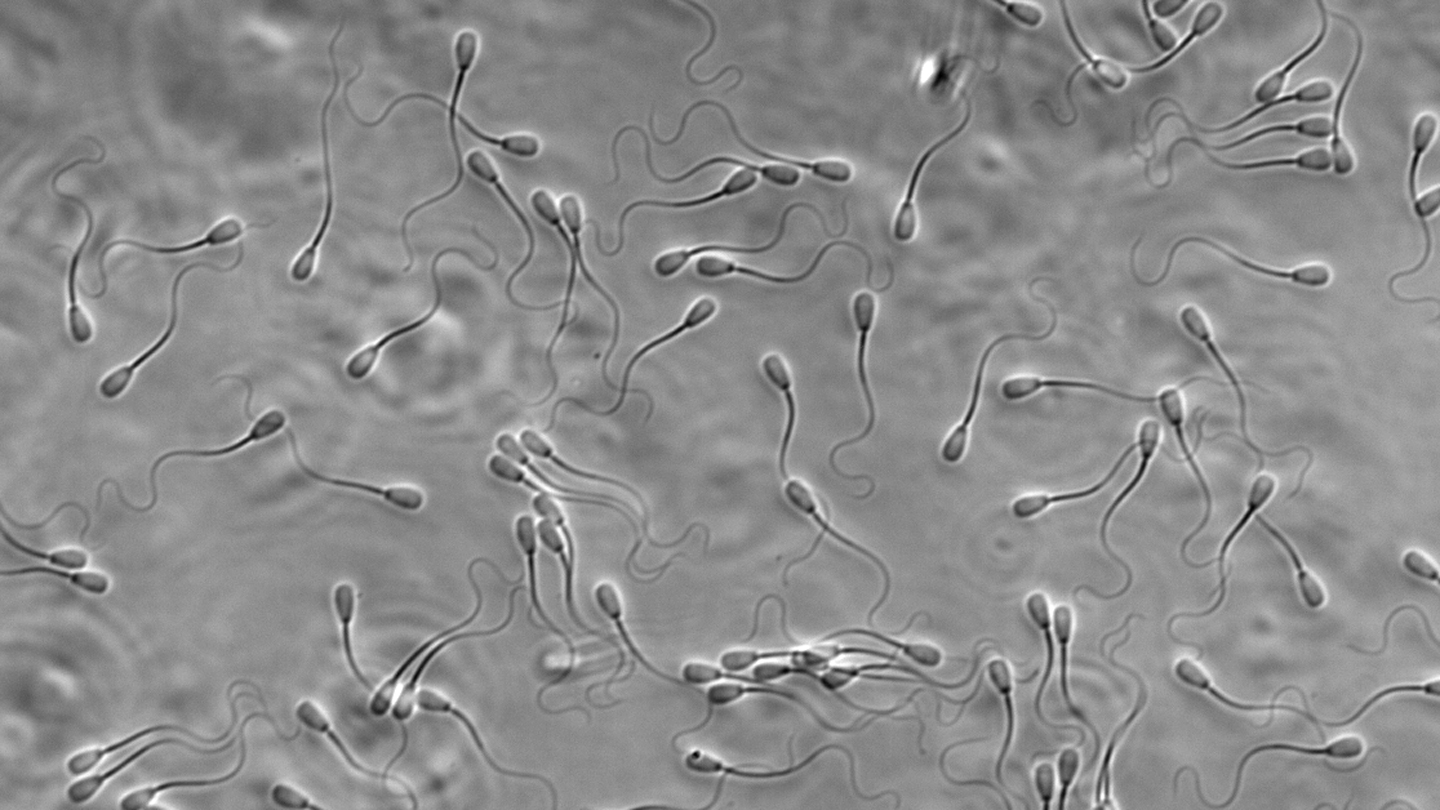

Bull sperm swim extra successfully when in clusters, a brand new research reveals, probably providing perception into fertility in people. In simulated reproductive tracts of animals like cattle and people, the habits will increase the possibilities that teams of cooperative bovine sperm will outpace meandering loners as they race to fertilize a feminine egg cell, physicist Chih-kuan Tung and colleagues report September 22 in Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology.

The advantages of clustering don’t come all the way down to flat-out pace. “They are not faster,” says Tung, of North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University in Greensboro. “In terms of speed, they are comparable or slower” than sperm touring alone. Like the sperm equal of herds of tortoises racing particular person hares, the winners will not be essentially the swiftest however moderately those that may keep on track.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the newest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Thank you for signing up!

There was an issue signing you up.

On their very own, sperm are inclined to comply with curved paths — which is an issue, as a result of the shortest distance between two factors is a straight line. But when sperm collect in teams of two or extra, they swim alongside straighter routes. It’s habits that a few the identical researchers famous in a earlier research the place they tracked sperm swimming in stationary fluids (SN: 3/17/16). Although that may give sperm clusters a bonus, it could solely assist in the event that they occur to be going the precise route. Other advantages of sperm clustering weren’t clear till the researchers developed an experimental setup that launched flowing fluid into their experiments.

In creatures like people and cattle, sperm make their method to the ovum by swimming towards a present of mucus that streams by the cervix and away from the uterus. It’s troublesome to review what advantages clustering may confer whereas swimming upstream inside dwelling beings. So Tung and colleagues created an analog of their lab: a shallow, slim, 4-centimeter-long channel stuffed with a thick fluid that mimics pure mucus and flows at charges the researchers might management.

Whether alone or in teams, sperm naturally are inclined to swim upstream. However, clusters of sperm within the experiment did a greater job heading upstream into the mucus stream, whereas particular person sperm had been extra prone to head off in different instructions. Despite the faster travels of some particular person sperm, a poorer skill to level upstream hampered the progress of sperm loners in contrast with slower shifting clusters.

In a thick, mucuslike fluid flowing from left to proper, clusters of sperm journey extra constantly towards the stream than particular person sperm do on their very own.

Clusters additionally stayed the course within the face of quickly flowing mucus. When the researchers turned up the stream of their equipment, many particular person sperm had been washed away. Sperm clusters had been a lot much less prone to get swept downstream.

While sperm within the research had been bovine, the benefits of clustering must also apply to human sperm, Tung says. Sperm of each species have comparable dimensions. The swimmers usually compete to fertilize a single ovum. And in contrast to pigs or different animals the place semen is deposited immediately within the uterus, each human and bovine sperm begin out within the vagina and journey by the cervix to get to the uterus.

Studying sperm in fluids that intently resemble the flowing mucus in reproductive tracts might reveal issues that don’t flip up in typical observations of sperm swimming in stationary fluids, Tung says. “One hope is that this sort of knowledge can help us do better diagnoses” to supply clues to know infertility in people (SN: 3/31/03).

Subjecting sperm to practical settings within the lab might quickly provide sensible assist for individuals who have bother conceiving, says fertility researcher Christopher Barratt of the University of Dundee in Scotland, who was not affiliated with the research (SN: 6/9/21).

“How a sperm cell responds to its surroundings and how that may change its behavior is a very important subject,” Barratt says. “This type of technology could be used, or adapted, to select better quality sperm,” for folks in want of fertility help. “That would be a very big deal.”