Call it mobile life assist for useless pigs. A fancy net of pumps, sensors and synthetic fluid can transfer oxygen, vitamins and medicines into pigs’ our bodies, preserving cells in organs that will in any other case deteriorate after the center stops pumping.

The discovering, described August 3 in Nature, is preliminary, nevertheless it hints at new methods to maintain organs in a physique wholesome till they can be utilized for transplantation.

In earlier work, scientists constructed a machine they named BrainEx, which stored elements of mobile life chugging alongside in decapitated, oxygen-deprived pig brains (SN: 4/17/19). The new system, known as OrganEx, pushes the method to organs past the mind.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the most recent Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Thank you for signing up!

There was an issue signing you up.

“We wanted to see if we could replicate our findings in other damaged organs across the body, and potentially open the door for future transplantation studies,” says Nenad Sestan, a neuroscientist at Yale University School of Medicine.OrganEx goals to do the job of hearts and lungs by pumping a man-made fluid all through pig our bodies. Mixed in a 1–1 ratio with the animals’ personal blood, the lab-made fluid has components that present contemporary oxygen and vitamins, stop clots and defend towards irritation and cell dying.

Anesthetized pigs have been put into cardiac arrest after which left alone for an hour. Then some pigs have been positioned on an current medical system, known as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO. This provides oxygen to the pigs’ personal blood and pumps it into their physique. Other pigs obtained the OrganEx therapy.

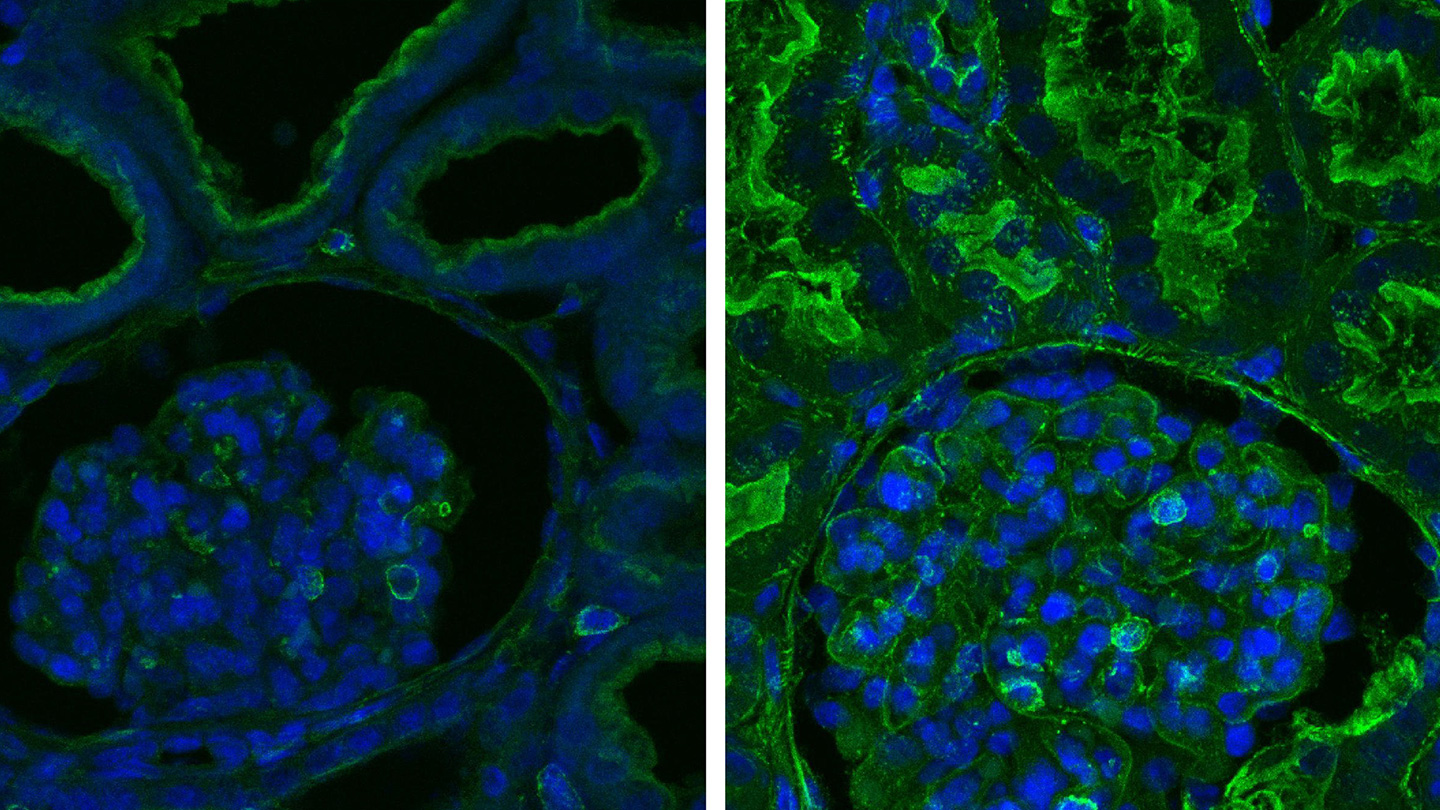

Compared with ECMO, OrganEx offered extra fluid to tissues and organs, the researchers discovered. Fewer cells died, and a few tissues, together with kidneys, even confirmed mobile indicators of repairing themselves from the injury accomplished after the center stopped.

The same system may sooner or later be helpful for shielding human organs destined to be donated. But for now, “there is still lots of work to be done in our animal model,” Sestan says.